Title: Is the Future of Central America’s Growth Sustainable?

Central America is a region in the Americas with potential for higher economic growth. For the regional economy to grow in a sustainable manner in the years ahead, policymakers must act on three fronts: economic diversification, workforce upskilling, and intra-regional cooperation.

Introduction

Because of the Central American Common Market and the region’s access to the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, Central America has a strategic trade and investment value for the major world economies. While the region has been growing more than Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) and continues to exhibit higher growth outlooks in the near future, it faces structural challenges in productivity and development that may compromise the region’s future economic performance. Policymakers and industry players across Central America are at a pivotal time to calibrate their trade, investment, and development policies to ensure the region strengthens its competitive position in the global economy. Potential gains for the region lie in diversifying all the Central American economies towards non-agricultural products while holistically investing in human capital.

Central America has Potential for Higher Growth

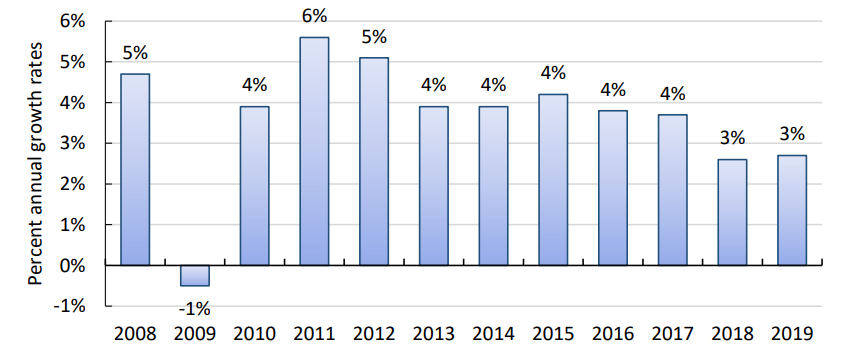

Central America’s economic growth has been slowing over the last decade. According to the International Monetary Fund, the region’s economy has been growing at a slower pace since 2011, when growth peaked. In that year, Central America attained a record high GDP growth rate of 5.6 percent, recovering from a financial crisis and exhibiting a positive outlook on regional prosperity for the coming years.

Figure 1: Central America’s GDP Growth. (2018-2019, in percent values)

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the International Monetary Fund.

In the years since the global financial crisis in 2009, Central America’s growth has decelerated to 2.7 percent in 2019. Though Central America has maintained steady growth rates, countries across the region have exhibited varying economic performance. In 2019, Panama grew by 4.3 percent while Nicaragua’s growth declined by 5 percent. Current projections estimate that Central America could grow by 3.7 percent in 2023, with Panama and Guatemala leading the region’s economic growth.

The steady growth rates of Central America have been attributed to sound conditions of macroeconomic stability conditions. A recent McKinsey report highlighted that the region has maintained lower levels of inflation, foreign exchange volatility, public debt, and fiscal deficit in comparison to the rest of Latin America and other developing economies over the past five years. However, government debt across Central American countries has been rising in recent years, which could jeopardize the region’s economic growth. IMF calculations indicated that the Central American government debt as a proportion of the region’s GDP peaked at 43 percent in 2019, with El Salvador and Costa Rica reporting 68.3 percent and 57.1 percent respectively. These debt levels are above the tacit rule that public debt should not be higher than forty percent.

Trade has played a role in boosting the region’s economic growth throughout the years. Central America published its General Treaty on Economic Integration on December 13, 1960. All Central American countries joined this treaty in 1963, with the exception of Panama. This integration process was interrupted by Guatemala’s Civil War in 1960, followed by the Civil Wars of Nicaragua and El Salvador in the 1980s. Since the post-war era, Central America has strived towards deeper economic integration that increases the region’s participation in global markets and economic growth. The Inter-American Development Bank estimates that a completion of pending intra-regional trade agreements could boost Central America’s regional and total trade by 56 percent and 6 percent respectively, with the region’s real GDP increasing by 1.2 percent over the next decade.

Central America’s merchandise exports have been increasing over the past two decades. In the years since all countries joined the General Treaty on Economic Integration, Central America increased its exports at an exponential pace. Nevertheless, after peaking in 2012 with a record high value of USD fifty-six billion, the region’s exports decreased and stagnated at USD fifty-two billion on average between 2013 and 2018.

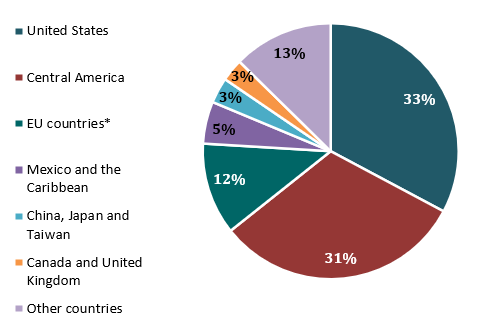

Central America is well connected with some of the world’s largest economies. Figure 2 shows the region’s exports by destination country on average between 2014 and 2018. The United States has remained the largest trade partner for the region, purchasing more than a third of Central America’s exports. Intra-regional exports in Central America are about the same size as those going to the United States. The region also trades with Europe and Asia, with five countries in the European Union (the Netherlands, Belgium-Luxemburg, Germany, Spain, and Italy), which purchase a tenth of Central American products while China, Japan, and Taiwan jointly make up 3 three percent of foreign purchasers.

Figure 2: Central American exports by destination (2014-2018, average percent distribution)

Figure 2: Central American exports by destination (2014-2018, average percent distribution)

Source: Author’s calculations based on the Secretariat for Central American Economic Integration (2020)

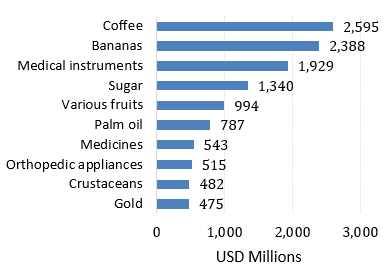

Figure 3 depicts Central America’s top ten export products between 2014 and 2018. Agricultural goods make up the majority of top exports, accounting for nearly a third of the total export value over the period. This statistic demonstrates that the region is relying on agricultural products for its exports growth, which tend to oscillate due to price volatility and climate change, among other factors. One example was the impact of coffee rust in Central America’s coffee production between 2012 and 2014. During these years, coffee production in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua diminished by seventy percent, twenty-three percent, eighteen percent, and fourteen percent, respectively. Prolonged dependence on agricultural products is a source of risk for Central America and can exacerbate the economic burdens the region already bears from extreme climate events.

Figure 3: Central American top 10 exports (Average values in USD millions over the 2014-2018 period)

Figure 3: Central American top 10 exports (Average values in USD millions over the 2014-2018 period)

Source: Author’s calculations based on the Secretariat for Central American Economic Integration (2020)

If this is the future of Central America concerning growth, what can the region change in order to facilitate sustained economic growth?

Education is Key for Lifting Up Regional Development Conditions

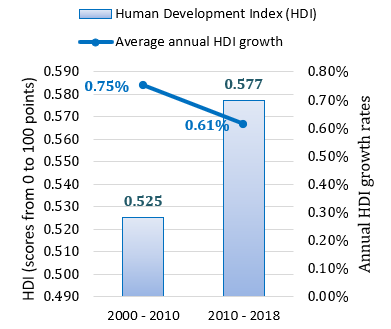

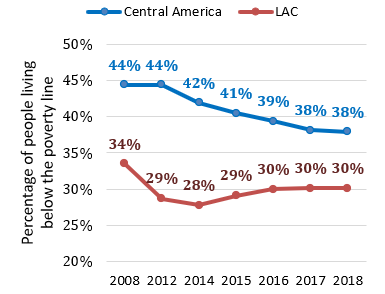

Maintaining economic growth at a sustainable pace is vital for Central America, in order to reduce poverty and economic inequality in the region. Figures 4 and 5 respectively show trends in poverty reduction and human development that Central America has recorded in selected periods over the last two decades.

Figure 4: Central America’s Human Development Index (2000-2018)

Source: Author’s calculations based on the United Nations Development Programme (2019a)

Figure 5: Central America and LAC’s poverty rates (2008-2018)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (2019)

Figure 4 presents Central America’s average performance on the Human Development Index developed by the United Nations Development Programme (2019a) during the periods of 2000 to 2010 and 2010 to 2018. Although Central America has been demonstrating steady increases in human development, its progress over the last decade has slowed in comparison to the growth seen between 2000 and 2010. Indeed, average annual growth rates on the Human Development Index for the region decreased by 0.14 percentage points between the two periods. When looking at the index components, Central America has made greater strides in raising general living standards measured by gross national income. However, the pace of growth in schooling years in the region has reduced considerably.

Central America’s higher living standards during the last decade were observed along with some progress in poverty reduction. Figure 5 shows that poverty rates in Central America decreased from forty-four percent in 2008 to thirty-eight percent in 2018. Despite this progress, poverty levels in Central America remain higher than elsewhere in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Conclusion

Central America is a region with high economic growth potential, something the region has demonstrated when not held back by global economic turbulence, such as that from the 2008 Financial Crisis. Despite its high exposure to international financial markets, the region has been growing at a steady pace and raising living standards. However, the region must diversify its economies, invest more in education, enhance intra-regional cooperation to remain competitive in global markets, and maintain sustainable levels of economic growth.

Continued reliance on agricultural exports and slower progress in schooling are two concerning factors preventing the region from attaining higher growth and development conditions. Upskilling the Central American workforce to be more qualified for non-agricultural sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing and services, represent strategic opportunities for Central American economies to increase their competitiveness in the global economy.

Policymakers should then focus their efforts strategically in three areas.

First, they should foster an enabling environment for greater business development opportunities in non-agricultural sectors of the economy. As the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is leading to sweeping technological and business changes in all economic sectors, policymakers could seize the momentum to calibrate industrial, competition, and technology policies to incentivize domestic and foreign investment in Central American countries. Some countries have already defined national plans for increasing competitiveness, productivity, and innovation. For example, newly elected authorities in Guatemala formulated the National Plan for Innovation and Development 2020 – 2023 that aims to foster e-commerce business opportunities and increase technological innovation capabilities across economic sectors. Costa Rica, on the other hand, adopted a National Decarbonization Plan in February 2019 to achieve a zero carbon economy by 2050. Thus, governments and businesses could collaborate on improving the financial, regulatory, and educational conditions that are essential for investors, entrepreneurs, and business owners to create new businesses and employment opportunities.

Second, policymakers should implement long-term education programs that upskill the current and future labor force to be qualified for new businesses emerging in the manufacturing, services, and technology sectors. Though Central America has made strides in raising living standards, education progress has slowed over the past decade. Education is a key area where public, private, and civil society actors could jointly work to address the structural problems that have been leaving most of the Central American countries behind in quality of education. Looking forward to the next decade, Central America will have a new demographic bonus, and this represents an opportunity for the region to modernize education institutions and training tools along with enhancing employability conditions for the workforce.

Third, Central American leaders are at a pivotal point in history to resume their regional cooperation. As a new industrial revolution may have an impact on the region’s economic, fiscal, and financial performance, strengthening Central America’s position in the global economy is crucial. With evidence suggesting that completing pending intra-regional trade agreements could boost the region’s output and trade, policymakers could then define a strategic roadmap that enhances regional integration and cooperation on issues that often hold investors and entrepreneurs back from doing business, such as political stability, good governance, and institutional property rights. In this way, Central American leaders could seize the benefits of acting as a unified commercial block to sustain the region’s economies amid uncertainty and systemic changes.

. . .

Sergio Martinez is an international economist and data analyst with over eight years of experience at various public and private institutions, including the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund. He is currently a trade and sustainable development consultant, whose work focuses on small business finance and impact investment.

Dr. Mauricio Garita is the Director of the Master in Finance and the Co-Director of the Master in Real Estate Development at the Universidad Francisco Marroquín. He is also the former Associate Editor for Latin America of the International Journal of Business and Emerging Markets.

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…