Title: COVID-19 and Organized Crime: the Politics of Illicit Markets, States, and the Pandemic

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic and governments’ efforts to stem the spread of the virus, some forms of crime and violence declined in Latin America. But the reprieve was temporary as levels climbed back, in some places to record levels. More broadly, however, the pandemic and its economic and social impacts are altering how criminal organizations across Latin America govern societies, economies, and politics.

COVID-19 is challenging state capacity in Latin America as political leaders scramble to stem the rate of infection and vaccinate their populations in a region that is among the most unequal in the world. But COVID-19 has intersected with the region’s other ongoing pandemic: criminal violence. For some time now, Latin America has had the world’s highest per-capita homicide rate and accounted for roughly one-third of the world’s murders each year. While the virus may have initially dampened levels of crime, the effects of the pandemic run even deeper as diverse criminal organizations across the region reconfigure the ways in which they influence everyday community dynamics, the operation of both licit and illicit markets, and politics and governance.

Crime and Violence During the Pandemic

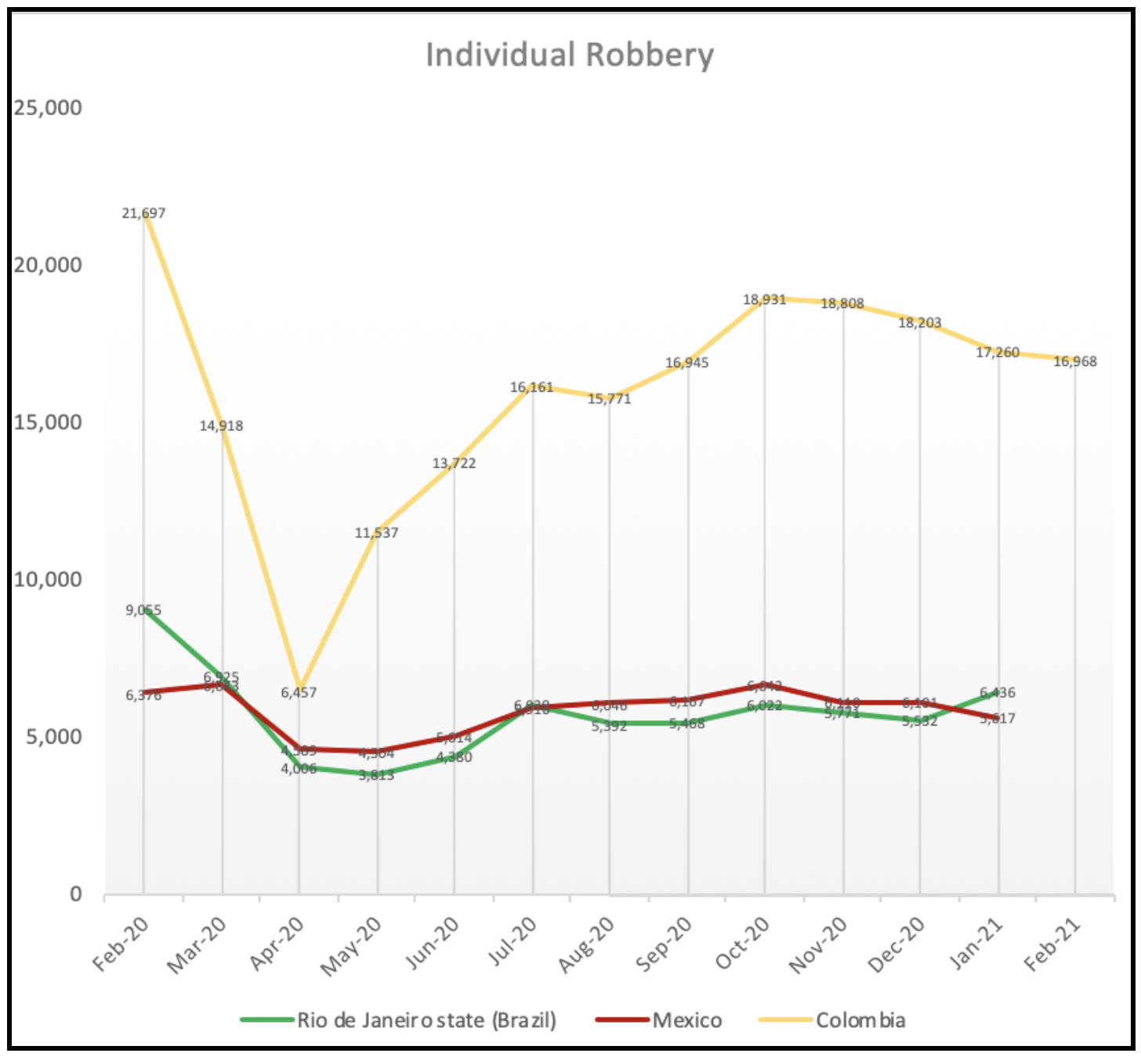

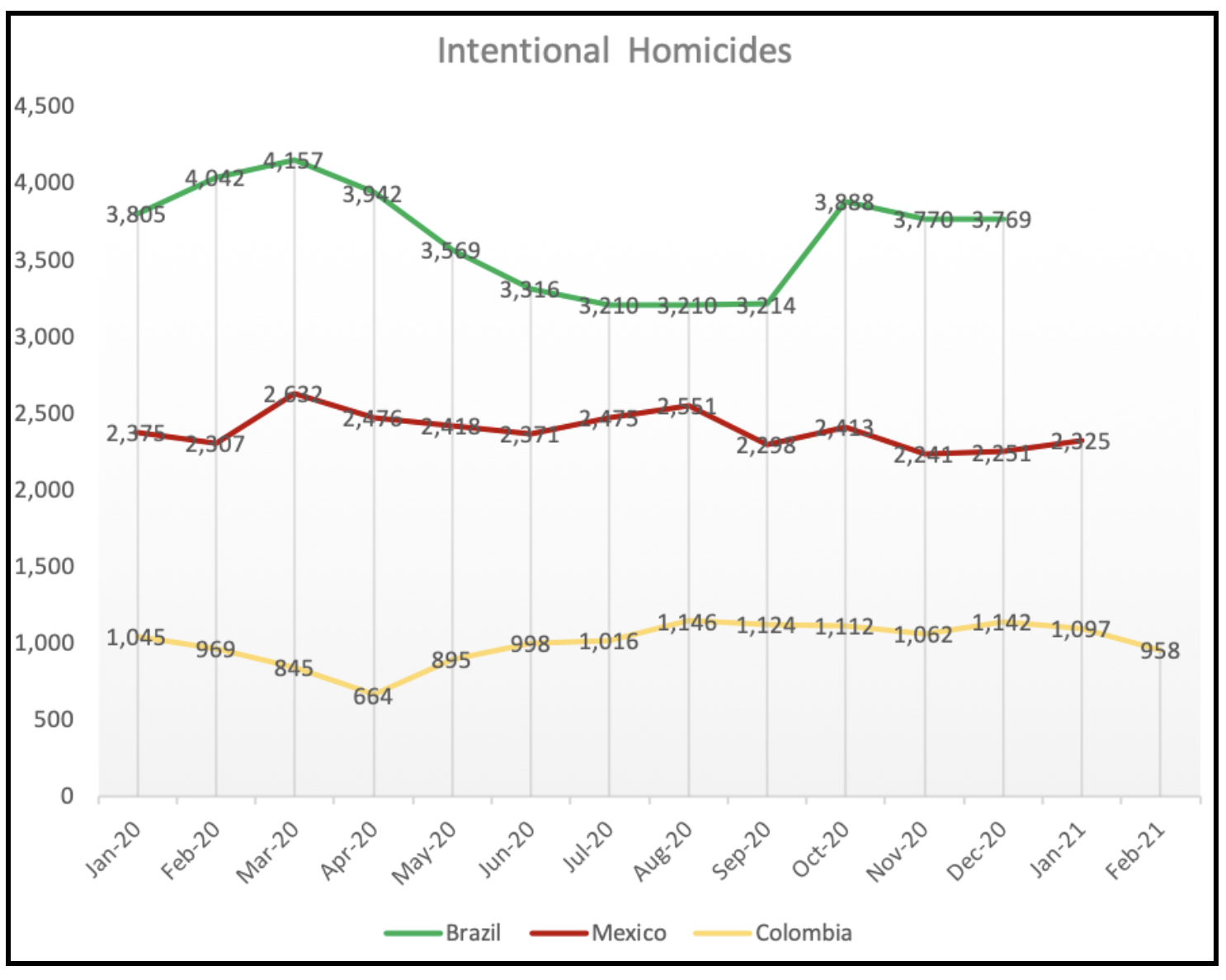

The COVID-19 pandemic initially dampened some of the most visible forms of crime and violence in Latin America, as evident in three parts of the region most hard hit by the virus and with long histories of organized crime. Figure 1 shows that individual robberies during the first quarter of 2020 declined steeply in Colombia and later in Mexico. Even in the state of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil – infamous for both organized crime and repressive policing – the number of robberies declined sharply in early 2020. People spending more time at home either voluntarily out of fear of contracting the virus or in response to government-imposed social distancing measures likely reduced opportunities for theft and other “street crimes” by curtailing mobility in public spaces. Figure 2 shows that whereas the national number of homicides declined in Colombia at the start of 2020, they increased in Mexico and Brazil during the first quarter of the year. But as governments relaxed social distancing measures and population mobility resumed later in 2020, the rates of crime and violence also returned to their pre-pandemic “normal” levels. While not all street crime or lethal violence can be directly attributed to organized criminal groups, all three countries are renowned for the presence of powerful criminal organizations responsible for substantial shares of crime and violence. But the criminal landscape has not simply returned to the status quo. Instead, organized criminal groups have had to adapt in how they influence patterns of everyday life, markets, and governance in the region.

Figure 1. Individual robbery cases in Mexico, Colombia, and the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro

Figure 1. Individual robbery cases in Mexico, Colombia, and the Brazilian state of Rio de Janeiro

Figure 2. Intentional homicide cases in Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia

Figure 2. Intentional homicide cases in Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia

Organized Crime Adapting to the “New Normal”: Licit and Illicit Economies

The pandemic is highlighting the intertwined nature of licit and illicit economies. Reduced global trade in 2020 stunted economic activity and closed national borders, hampering Latin American drug cartels’ production and trafficking capacities and limiting the access of drug cartels to precursor chemicals from China necessary to manufacture drugs like methamphetamines. Latin America is the source of much of the illicit narcotics consumed in the United States: cocaine production is concentrated in the Andes, heroin in Mexico, and Central America and Mexico serve as key transport corridors. But the slowdown in global trade also cut into cartels’ ability to smuggle drugs across borders given that the majority of illicit narcotics enter through legal points of entry at border crossings, seaports, and airports. The changes in the global drug trade are having broader societal repercussions in both producer and consumer nations. For example, the price of coca, the natural basis for cocaine, has dropped in parts of Latin America by over seventy percent, negatively impacting the subsistence farmers that rely on the crop to make ends meet. Meanwhile, reduced supply has inflated the price of cocaine in consumer markets in the United States and parts of the developing world—a trend that could contribute to levels of crime in the long run as users turn to delinquency in an effort to finance an increasingly expensive addiction.

But the pandemic is also generating incentives for organized crime groups to deepen their involvement in other illicit economies. Today, organized criminal groups involved in the drug trade are just as likely to participate in a range of other illicit markets that further blur the boundaries between legal and illegal economies. For example, prior to the pandemic, both drug cartels and the criminal gangs they enlist for street-level drug sales were also engaged in systematic extortion of both formal and informal businesses as a prime generator of profits. As part of extortion, criminal groups in Colombia often oversee high-interest loans that their victims use in settings where formal credit for businesses is scarce. As the economic situation in Latin America deteriorates under the pandemic, this could lead more people and businesses to turn to such informal credit lines, further strengthening the economic capacity of criminal actors.

Prior to the pandemic, organized crime in Latin America had started incorporating profitable trade in illegal timber logging and exotic wildlife trafficking into its illicit portfolio. In both cases, profitability is dependent on the strength of licit markets. In parts of Mexico, complex arrangements between timber, drug trafficking organizations, and sawmills enable the mixing of illegally and legally harvested timber that is then sold to formal construction firms and other legal economic sectors. Illegal wildlife trafficking similarly relies on legal flows of people and goods to transport illegally captured exotic birds, reptiles, and sea animals, among other wildlife, to consumers in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Growing unemployment due to the pandemic in countries such as Brazil has led to a boom in wildlife trafficking as criminal organizations encounter more people willing to engage in this illicit industry to make ends meet under difficult economic circumstances.

Organized Crime, States, and Governance

In spaces where criminal groups operate and state presence is limited, gangs and other criminal groups have stepped in to meet the needs of populations. Powerful gangs in Brazil are enforcing quarantine policies—at times violently. In Mexico, the daughter of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, the former leader of the Sinaloa drug trafficking organization, appeared in globally circulated photographs filling boxes—branded with images of her now-incarcerated father—with food and other basic necessities for distribution in Guadalajara. Benevolent actions like these can help criminals build legitimacy in the eyes of the populations where they operate and, in turn, solidify their control over territories where the state is absent or weak. Yet, the cost of distributing some basic supplies is likely dwarfed by the immense revenues drug cartels bring in from the illicit drug trade. The very fact that criminal organizations are allowing photographs and videos of them to be recorded, or in some cases purposefully disseminating them, suggests an effort to bolster their territorial control and, more broadly, make clear yet again that states are not the only authorities throughout much of the region.

Moving Forward: Building State Legitimacy in the Face of Organized Crime

How can Latin American governments respond to the pandemic in ways that could arrest some of these trends outlined above? So far, governments have turned to the armed forces for quarantine enforcement, but the militarization of policing when institutions of accountability are weak is dangerous. In Honduras, for example, military troops have been accused of beating and even killing several individuals that broke quarantine restrictions in different parts of the country. More broadly, the armed forces may not be easily convinced to return to the barracks once the pandemic subsides and will likely leverage looser constraints on their behavior to continue or increase their role in fighting crime. But the militarization of policing often leads to human rights abuses because armed security forces trained to engage in armed conflict lack the training necessary for the very different task of policing civilians. Nonetheless, because crime is such a politically salient issue across Latin America and there is widespread demand for order, politicians may be tempted to leverage the ongoing pandemic to harden their stances on crime in ways that further erode human rights and democracy but consolidate political support.

Governments should instead increase social assistance to the populations most vulnerable to the socioeconomic fallout from the pandemic. Here, the pandemic paradoxically provides Latin American governments with an opportunity to reclaim authority and legitimacy from the hands of criminal actors. Governments should target public investment to communities where criminal actors hold territorial control. Direct cash transfers to households and investment in local public infrastructure, from health clinics to cultural centers, could signal to communities long politically and socioeconomically marginalized that the state is committed to enabling them to fulfill their citizenhood. Providing the region’s vast number of informal businesses with access to credit to help weather the economic downturn would also reduce their vulnerability to the high-interest loans that criminal extortionists and loan sharks throughout the region offer. Targeted public investment could alter the balance of power between criminals and states precisely in those territories where citizens and state institutions are most struggling to keep afloat in the face of powerful criminal organizations.

. . .

Eduardo Moncada is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Barnard College, Columbia University. His research focuses on the political economy of crime and violence. He is the author of the forthcoming book, Resisting Extortion: Victims, Criminals, and States in Latin America (Cambridge University Press).

Gabriel Franco is an undergraduate student at Columbia University and research assistant at the university’s Institute of Latin American Studies.

Image Credit:

Recommended Articles

This paper examines the interrelated crises facing the Maghreb region: water scarcity and gender inequality. It describes the current approach towards addressing water scarcity and how incorporating women’s voices into…

This article compares U.S. and Chinese approaches to artificial intelligence (AI) exports in Africa and examines how these disparate approaches have produced both downstream benefits and challenges for the region.

On May 20, 2025, the World Health Assembly unanimously adopted the World Health Organization (WHO) Pandemic Agreement, an international treaty designed to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness, and…