Title: Preventing the Next Systemic Emerging Markets Debt Crisis: Debt Affordability for Emerging Markets in a Post-Pandemic World

The pandemic has already widened the inequality between advanced economies (AEs) and emerging markets[1] (EMs). The rising interest burden in EMs, if unchecked, will divert precious fiscal resources that can be put toward economic development priorities. At worst, it may lead to widespread sovereign debt crises. This essay contextualizes the debt affordability[2] challenges facing EMs and recommends immediate actions that may durably support debt affordability.

The hysteresis to sovereign debt affordability for emerging markets due to the pandemic is difficult to overstate. The financial resources of most EMs are already strained from the collapse in revenues, and that may take years to recover. At the same time, higher debt burdens are increasing debt service costs. Together, these two dynamics are placing acute pressure on debt affordability and sovereign creditworthiness that may take several years to reverse, and a return to higher global interest rates would exacerbate this situation. This severe and persistent deterioration in EM sovereign creditworthiness should be viewed as a crisis, even if it doesn’t lead to widespread or systemic EM sovereign defaults. When juxtaposed against advanced economies, where debt affordability is improving, these conditions would amplify the AE-EM inequality.

These conditions call for aggressive, immediate, and sustained efforts from global and national-level policymakers. What realities underlie the troubling trajectory of sovereign creditworthiness and debt affordability? What can be done to support debt sustainability and mitigate pressures on debt affordability? The messages and early initiatives from the G20, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and World Bank Group (WBG) are appropriate given the realities that underlie the troubling trajectory of sovereign creditworthiness and debt affordability, but much more needs to be done to support debt sustainability and to mitigate pressures on debt affordability. Policies that have immediate benefits as well as some longer-term initiatives which can yield outsized benefits that are long-lasting must therefore be prioritized.

While the pressure on debt affordability is common to almost all EMs, the policy responses will need to be calibrated to the specific characteristics of a country’s debt profile. EMs are a highly heterogenous group in terms of the different financing risks they are exposed to. Low-income developing countries (LIDCs) are the most resource-constrained with limited access to global capital markets, but they benefit from concessional funding. At the other end of the spectrum are highly-rated (mainly investment grade) EMs that typically have unfettered market access; their debt is mostly denominated in their own currency, they can issue at long tenors (reducing refinancing risks), and they have reasonably deep domestic capital markets. Most countries in this group are not susceptible to sharp currency depreciations or sudden stops in capital flows, but they may still face growing pressures on debt affordability due to rising debt stocks in their own currency. In the middle, there are EMs that still have significant reliance on foreign currency-denominated borrowing from capital markets.

Hysteresis and the K-shaped Trajectory of Sovereign Creditworthiness

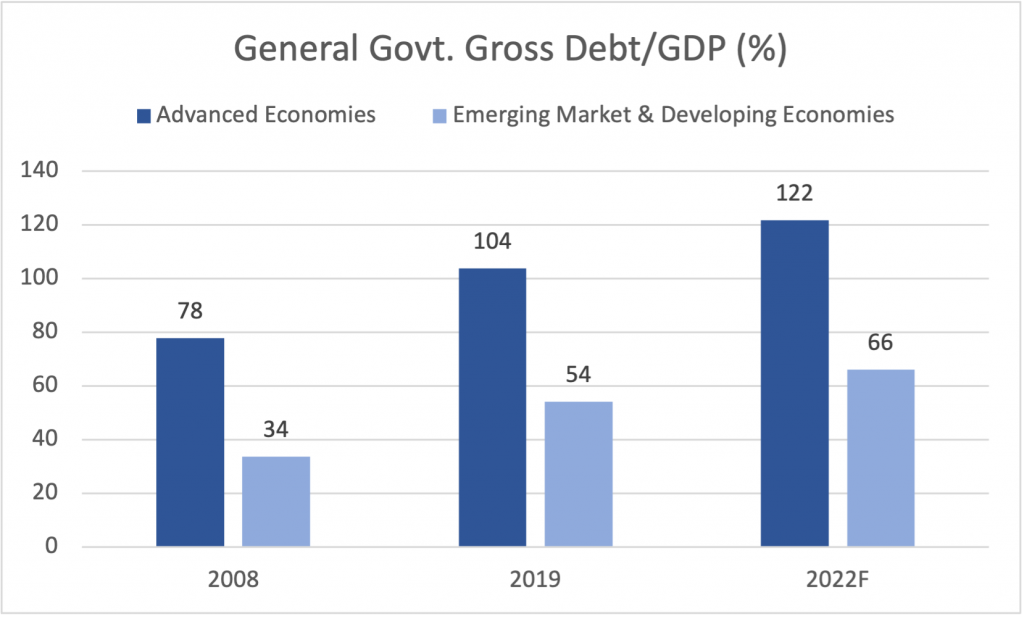

The pandemic is intensifying prevailing adverse trends in EM sovereign creditworthiness and making them harder to reverse. Debt affordability for EMs had already declined between the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the COVID-19 Crisis. Based on IMF data, AE government indebtedness rose by 26 percentage points in the decade after the GFC and will have risen by another 18 points in the immediate wake of the pandemic (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: General Government Gross Debt/GDP (%)

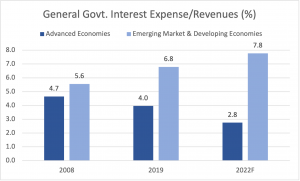

In the same periods, the numbers for EMs are 20 and 12 percentage points—seemingly more modest. However, debt affordability has sharply diverged. By 2022, relative to a decade earlier, EM’s affordability will have worsened by around 50 percent, whereas for AEs it will have improved by around 50 percent (see Chart 2).

Chart 2: General Government Interest Expense/Revenues (%)

AE debt affordability has been supported by the impressive capacity of their central banks (mainly via quantitative easing) to further suppress borrowing costs that were already low by historical standards.

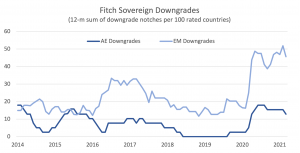

In addition to the proximate economic conditions that are placing EM creditworthiness under pressure, there are political and institutional factors that are adding headwinds. EMs (and even some AE sovereigns) have been suffering from an underappreciated crisis of institutions that predates the onset of the pandemic. Across many EMs, political conditions have led to inadequate focus on institutions and prioritizing the economy. Collectively, this crisis of institutions has reduced the institutional capacity to formulate economic policies that are conducive to stronger economic outcomes and made them less effective in crisis response. Rating agencies have already downgraded a disproportionate share of EM sovereigns during the pandemic leading to a further divergence in creditworthiness (see Chart 3).

Chart 3: Fitch Sovereign Downgrades

Popular discontent arising from post-pandemic conditions—rising inequality and falling standards of living for the underprivileged—may worsen governability and political stability in many EM countries. This is likely to exacerbate prevailing pressure on sovereign creditworthiness. This outlook is probably not reflected in current borrowing costs, as easy global financing conditions and the search for yield underway since the GFC continue to distort market pricing of debt. The pandemic may test the social contract in many EMs, distracting political leaders from focusing on longer-term economic issues and creating downside risks to creditworthiness and financing conditions for EMs.

The Way Forward: Shifting from a K-Shaped Trajectory to Convergence

Much of the onus to repair debt affordability lies with the political leadership and national-level policymakers, but all stakeholders may consider bolder and more innovative actions. National-level policymakers have rightly been urged by the IMF to address the immediate public health crisis, to prevent more severe output and job losses, and to limit broader economic scarring. The efforts of the G20 and IMF-WBG towards providing emergency relief and expansion of Special Drawing Rights are commendable. The following recommendations would be beneficial for debt affordability:

- Reconsider broad debt forgiveness by the IMF-WBG. The main official sector efforts underway (G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative and the Common Framework) only cover seventy-three countries and excludes the majority of their debt, which is owed to multilateral institutions. Policymakers may consider relief measures that are more transformative. The principal shareholders of the IMF-WBG may initiate ways to convert a greater share of loans to grants. The shareholders have the financial wherewithal, and the lending institutions have the intellectual and technical capacity to implement such an initiative.

- Policymakers might adopt more realistic assessments of debt sustainability and more timely decisions regarding debt restructurings. Growth rates, primary balance targets, and interest rates—the key drivers of debt sustainability assessments—are more uncertain than ever. A more cautious and realistic view of these variables may facilitate earlier recognition of problems. It is advisable to do this while global financial conditions are still easy so that newly issued debt can lock in currently low interest rates. Policymakers and market participants may well rethink the trade-off between undertaking timely restructuring, or other liability management exercises, versus waiting until the problem forces a costlier outcome.

- Leverage IMF-WBG capital to crowd in private capital. The IMF-WBG may consider guarantees or other structured facilities that can provide more leverage—with less balance sheet pressure—than direct lending. And because many local companies have gone bankrupt (while better-resourced larger MNCs have gained market share), there is theoretically a larger role for the International Finance Corporation to augment the private sector investment envelope.

- Prioritize investments in institutions and social cohesion. Multilateral development institutions may significantly boost technical assistance towards strengthening the capacity of economic institutions, particularly those responsible implementing stronger fiscal frameworks, strengthening revenue mobilization, and increasing the efficacy of basic public services.

- Policymakers may adopt more of a “risk manager” mindset. Policymakers rightly focus on the central scenario, but would benefit from planning for downside scenarios too. When it comes to managing the fiscal impacts of financial volatility (from interest rates, commodity prices, etc.), there are a range of financial markets instruments that can help. However, institutional capacity at the national policymaking level is needed to ensure transparency and suitability around the use of such instruments.

[1] The term emerging markets (EMs) will be used to encompass all emerging markets and developing economies; the latter also includes low-income developing countries (LIDCs).

[2] For simplicity, debt affordability in this paper is defined as general government interest expense as a share of general government revenue. Related concepts include liquidity and solvency. In general, a worsening of debt affordability will also adversely affect liquidity and solvency. All of these concepts inform overall sovereign creditworthiness.

. . .

Nehad Chowdhury is a Managing Director and Global Head of Country Risk Management at Citigroup. He was previously an economist at the International Monetary Fund and head of emerging markets sovereign financing for EMEA at Goldman Sachs. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect that of institutions where he has worked.

Image Credit: Flickr, Joshua Roberts, Creative Commons License 2.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…