Title: State-Owned Enterprises’ Responses to China’s Carbon Neutrality Goals and Implications for Foreign Investors

As decisive pillars of the national economy, Chinese State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) have been seeking to help the country meet its carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals since the government announced them in 2020. New investment opportunities benefiting both foreign investors and SOEs are emerging in critical sectors for China’s carbon neutrality, including green finance, renewables, energy efficiency, electronification, hydrogen, and others. Unfortunately, these opportunities come with risks brought about by tightening political and regulatory situations, geopolitical tensions, pandemic response policies, and potential competitors.

SOEs as two-faced actors in China’s climate actions

SOEs play a wide variety of roles within China’s national settings. There are 97 central SOEs directly overseen by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC) and over 460,000 branches and sub-enterprises across the country. SOEs’ business ranges from traditional energy industries, such as coal, oil and gas, to energy-intensive industries, like iron, steel, and cement, to transportation, infrastructure, and financial sectors. In 2021, these 97 central SOEs—along with thousands of other SOEs in the hands of provincial and local governments—together accounted for 66 percent of GDP and 31 percent of tax revenue in China. Overall, SOEs are not only decisive players in China’s economy across many industries, but also the leading responders to public polices at all levels.

SOEs are major energy producers, consumers, and, subsequently, CO2 contributors in China. The top five electricity generators are all state-owned, and the largest among which, thermal power giant Huaneng Power International, produces 317 million metric tons of emissions per year; this is close to the annual emissions level of the United Kingdom. Similarly, China State Grid and China Southern Power Grid, the two SOEs that control the entire country’s electricity distribution and transmission, account for around 49.6 percent of Chinese CO2 emissions. The coal-related SOEs—emitting 4.61 billion tons of equivalent CO2 annually—form the crucial political opposition in China that counters aggressive climate policies and the phasing-out of coal.

Interestingly, China’s SOEs are also the biggest clean energy investors and developers, especially in the deployment stage. In 2020, solar PV SOEs were responsible for 83 percent of large-scale grid-connected PV power plants in China. As of today, SOEs are responsible for 65 percent of new wind capacity added to the grid. Additionally, the national development bank China Development Bank provided substantial support to renewable energy development and deployment, with more than 200 billion RMB invested by the bank in the 2010s.

Responses from SOEs to China’s carbon neutrality commitment

In September 2020, China made the historic announcement that CO2 emissions would peak before 2030, with net zero emissions achieved before2060. In November 2021, the SASAC put forward the Guidance on Promoting High-quality Development of central SOEs in Achieving Carbon Peaking and Carbon Neutrality, deciding on the SOEs’ demonstrative and leading roles. It requires that SOEs reduce their CO2 emissions per ten thousand yuan of output value by 18 percent by 2025 compared to 2020 and by 65 percent by 2030 compared to 2005.

SOEs quickly responded to the central government’s carbon neutrality goals. The State Grid Corporation became the first SOE to release its carbon neutrality action plan in 2021, and other SOEs such as PetroChina and China Development Bank followed shortly after by making their own carbon reduction and green investment commitments. According to SASAC, most SOEs have already set their peaking targets, most of which are in line with the national target of reaching carbon peak by 2030 or even more ambitious. 20 of the 97 centrals SOEs have established clear roadmaps and pathways geared towards reaching the 2060 carbon neutrality goals.

State-owned generators are actively enlarging their investments in low-carbon technologies and projects to ensure compliance with the carbon neutrality targets and facilitate green transformation. For example, China Huaneng Group has spent approximately 70 percent of its annual investment in low-carbon clean energy since 2010. Several major SOEs also made clear plans to provide headway for advanced clean technologies, including Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS), smart gird system, ultra high voltage (UHV) grid, hydrogen energy, green vehicles, and electrification. For instance, a data center in Beijing has implemented an AI energy-saving technology for cooling systems self-developed by China Telecom that can reduce around 3,740 tons of CO2 on an annual basis.

Besides direct investment, SOEs are also engaging in green finance. Giants including Sinopec, State Power Investment Corporation, China Energy, and Huaneng Group have issued a total of 11.1 billion RMB of green bonds mainly allocated to clean energy such as hydro and wind power projects as of March 2021. In December 2021, China Power Investment Corporation (SPIC) and China Life Asset Management jointly an 8 billion RMB clean energy fund, which is slated to be invested in 75 clean energy projects.

In terms of institutional reform, according to the SASAC guidelines, executives in SOEs are assessed by their performance in promoting carbon reduction, and those who do not meet the carbon reduction targets will be criticized and held accountable. Executives may be penalized or demoted in their annual assessment for making false data on CO2 emissions. As a result, SOEs are gradually establishing monitoring and evaluation (M&E) mechanisms that directly report to SASAC.

However, the mission is far from complete. Only about 64 percent of the listed SOEs have disclosed their ESG/CSR reports in 2022. Although more than half of SOEs have established individual carbon-related departments and businesses as of July 2022, some of them are merely symbolic arrangements. Moreover, most published plans do not clarify whether they cover Scope 3 emissions greenhouse gases of all types, and very few SOEs disclose their exact data on emissions to the public. Despite the difficulties involved in monitoring and calculating Scope 3 carbon emissions in the supply chains, SOEs can still lead by example through selecting green suppliers. For example, Anhui HeLi Co., Ltd, a leading enterprise in industrial vehicle production, tailors green products and services for different customer groups by evaluating and selecting suppliers with minimum resource consumptions.

Climate finance demands and implications for foreign investments

A systematic carbon neutrality transition requires substantial investments in China. Recently, China’s National Development and Reform Commission estimated that over 139 trillion RMB will need to be directed towards carbon reduction—much larger than what would be needed in the United States or Europe. These transition costs entail significant climate finance opportunities. Moreover, China has launched its national emission trading system, the largest in the world. Though the system only covers the power sector for now, it will gradually expand to all major energy-intensive sectors. It is estimated that the cumulative trading volume will exceed 100 billion RMB by 2030. As the government and SOEs cannot meet all these climate finance demands by themselves, China will depend on financial and technical support from private and foreign investors. As of now, more than a hundred SOEs have introduced a total of more than 253 billion RMB of private and foreign capitals. As for next steps, China will continue the “mixed ownership reform,” where private and foreign capitals are encouraged to involve in the SOEs’ reconstucturing through equity investment, acquisition of equity, subscription to convertible bonds, and many others.

There are potential risks that foreign investors need to be aware of when investing in Chinese SOEs. Though the government has declared its ambitions to develop CCUS and hydrogen, lack of concrete supportive policies and viable business models limits the scale of markets in the short term. Additionally, the political tension between China and the West in general undermines the trust among foreign investors in SOEs. Empirically, the US government has criticized and sanctioned Chinese SOEs for the lack of transparency. In August 2022, five Chinese SOEs with a combined market capacity of nearly $320 billion decided to delist from US Exchange as they were deemed “national-level Chinese [SOEs]” by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission for failing to meet U.S. auditing standards. Lastly, the dramatic shift of Chinese government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic has created significant uncertainties for foreign investors. At first, the domestic economic downturn due to the government’s rigorous pandemic control policies increased credit risks even if SOEs only accounts for a small number of defaulters. The Chinese government’s downgrading COVID-19 to a Category B disease and opening up its borders in 2023 released a seemingly positive signal to the world, but at the expense of skyrocketing COVID cases. In fact, the volatility of the COVID policy undermined the consistent market confidence from both domestic consumers and foreign investors.

Despite the risks associated with investing in Chinese SOEs, opportunities for foreign investors are prominent. Compared with SOEs or the local private sector, foreign investments will be appreciated as they provide cheaper finance and bring about advanced technology and good entrepreneurial practices across the world. Collaboration between SOEs and foreign investors can also be a win-win situation to explore in the future, especially in large-scale or demonstration projects. To the knowledge of the authors, certain SOEs are eager to resume collaborating with foreign firms in low-carbon technology development as they used to before the relationship between the United States and China became turbulent. SOEs are equipped with knowledge and skills well adapted to the locality and are usually monopolistic in their respective industries, which can help foreign investors expand their businesses into the vast Chinese local market. Besides, SOEs are backed up by the Chinese government, which reduces the risk of operations for foreign capitals.

However, given that most of the concerns from foreign investors lie in the lack of openness regarding the usage of the capital, Chinese SOEs should be more willing to be transparent about the technology they adopted, disclose information to the public, as well as create fair competitions by welcoming foreign capitals entering the local markets. These moves serve to reassure foreign investors the adherence of Chinese SOEs to basic market principles and international economic norms. SOEs should also internationalize their governance structure and enterprise culture to align themselves with their international peers. More international staff and globalized governance structure will make the collaboration process smoother. By reforming on their internal governance and integrating into the globalization, Chinese SOEs that are already domestic industry giants will be more likely to stand out in the global stage and entitled to be leaders across industries in combating climate change. They will be essential in boosting China’s soft power on the international stage and transforming the country into an indispensable member of global governance.

Conclusion

Chinese central SOEs are actively responding to the policy of carbon peaking and carbon reduction, with more and more SOEs in the process of making concrete plans to contribute to the national carbon neutrality target. The huge investment opportunities brought by carbon reduction goals benefit both foreign investors and SOEs. Foreign investors face the risks of potentially stricter regulatory rules, fierce competition with Chinese SOEs in clean energy sectors, geopolitical tension between China and the West, as well as volatile COVID policies, but greater transparency of Chinese SOEs in their business operations and internal governance will help dispel the concerns of foreign investors.

. . .

ZHANG Fang: An assistant professor from the School of Public Policy and Management, Tsinghua University

ZUO Jialu: A Master’s student from the dual degrees of Public Policy for Sustainable Development Goals, the School of Public Policy and Management, Tsinghua University, and Sciences de la société, Université de Genève.

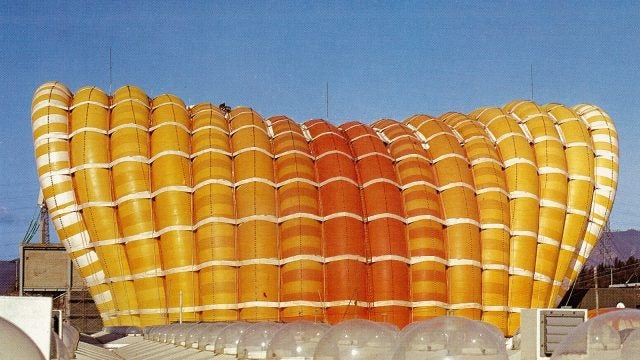

Image Credit: Picasa from Flickr, CC 2.0

Recommended Articles

Art and music serve as a shared language among all humanity. Yet historically, they have often been easily categorized into different genres or styles with little discourse on the intersection…

The Indonesian government under outgoing President Joko Widodo plans to relocate its capital away from Jakarta, a city that has been riddled with environmental and population challenges in recent years.

Across cultures and countries, food is a shared human experience, and different cuisines are a symbol of diversity. Yet, in our current climate crisis that requires sustainable solutions, we must…