Title: The Persistent Problems of the Olympic Games: A Focus on Paris 2024

Although beloved by billions around the globe, mega-events like the Olympic Games have a history of damaging the cities and societies that host them. Recent reforms by the International Olympic Committee have made progress in reducing some of these damages to host cities and societies. Still, certain problems persist, rendering the Games unsustainable in the long term. If the Olympic Games are to move towards authentic sustainability, an independent body must be established to regulate mega-events and punish organizers when such events harm socioeconomically disadvantaged groups. Affected residents must also have the power to determine which mega-events occur in their city, and how.

Reforming the Problematic Games

The Olympic Games are a mega-event: a global, mobile celebration of sport and culture that attracts worldwide attention, costs and generates fortunes, and critically alters physical and social landscapes. The Games have a history of damaging the cities and societies that host them. Negative consequences of hosting the games often include broken budgets that burden the public purse, oversized “white elephant” infrastructure, the militarization of public space through the introduction of new surveillance technologies and security practices, and the expulsion of residents through sweeps, gentrifications, and evictions. Despite touting their “green” credentials, recent Olympics continue this trend of damage: the gains of Beijing 2022 came at the expense of residents, and the sustainable procurement practices of Tokyo 2020-2021 were little more than greenwashing. Overall, measuring social, economic, and ecological sustainability since 1992 demonstrates that the Olympics are unsustainable.

These negative outcomes have generated waves of bad press globally, and cities have backed away from wanting to host. Protest movements opposing bidding and hosting plans have proliferated and, in some cases, have spurred public referendums or even canceled bids outright. For its part, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) has recently engaged in a wide-ranging series of organizational reforms. Under these new reforms, Olympic authorities have promised to adapt the Games to the city, rather than having the city adapt to host the Games as was previously the case. One important outcome of these reforms is the emphasis on using existing venues and infrastructures rather than requiring host cities to build new, expensive venues and other facilities for hosting. Other initiatives also helped reduce costs and streamline operations, including a reform to the bidding process and changing the timing of planning processes to reduce overspending. These reforms sought to mitigate hosting-related damages, restore the popularity of the Games, and put the Olympics on a sustainable path moving forward. The Summer Olympic Games in Paris 2024 were the first to be planned and delivered under these reforms.

Paris 2024 displayed some successes in reforming the Games toward more sustainable outcomes. The most important success in Paris was the high usage of existing venues, estimated at 80 to 95 percent. This bodes well for both ecological and economic sustainability, as the construction and later maintenance of oversized and underused sports venues has been a persistent problem with past mega-events. From Brazil 2016 to Athens 2004 to Montreal 1976, Olympic cities are littered with stadiums that are too large and expensive to build and maintain–one of the reasons that hosting has consistently gone over budget. In Paris, most new venues were temporary constructions such as the Grand Palais Éphémère, which will be dismantled after the Games. Mega-event scholars have long called for these steps. Hosting in existing buildings and only constructing temporary structures when needed should be celebrated and continued.

Problems in Paris

Despite this progress, problems with Paris 2024 persist. Much of the construction occurred in the communes that constitute the northern department of Seine-Saint-Denis, an economically disadvantaged and majority-minority banlieue known colloquially as the nine-three (the neuf-trois). Throughout the nine-three, Olympic-related projects have exacted a heavy toll on the locals. For instance, about 400 migrant workers were evicted to make room for the Olympic Village, which residents fear will lead to the gentrification of the commune. Alongside this eviction, at least sixty squats were cleared in areas near Olympic sites as a result of a new law that stiffens fines and simplifies legal proceedings concerning the occupation of public spaces. Some consider this an overdue step towards urban improvement, but others protest the inhumanity of the actions, as affordable housing remains out of reach for many. Squatters were forced out with no alternative housing plan in place for them. This is part of a city-wide process of “hiding the undesirables,” a longstanding tradition among host cities, as they prepare for the global spotlight. Thus, unfortunately, the Paris Olympics mirror the Vancouver 2010 and London 2012 Olympics when marginalized youth were swept out of sight before the event.

During the Games in Paris, both the tourist center and the nine-three witnessed an overwhelming police and military presence with omnipresent security barricades, severe restrictions on personal travel, and the introduction of AI-powered facial-recognition security cameras. While the mega-event must be secured against terrorist threats, these security practices were deployed against residents. One activist and resident of the nine-three was arrested, held for ten hours, and fined by the authorities when he tried to lead a small group of French journalists around the sites of Olympic intervention in Seine-Saint-Denis. When he tried again a few days later, he was met at the exit of the metro by authorities and arrested once more. Locals express concern that these technologies and practices will remain after the Olympics and fundamentally change the nature of public space in Paris and France more broadly.

Elsewhere in the nine-three, a highway interchange and offramp were recently constructed in the neighborhood of Pleyel, not far from the Stade de France, the official Olympic Stadium for Paris 2024. As part of the city’s longstanding plan to revitalize Pleyel by transforming it into a business and entertainment hub, this transport intervention was executed alongside an expansion and improvement in metro and train services. These investments were justified through the Olympics, another example of mega-events being used to overcome political obstacles in the host city. These plans, however, are controversial among local residents. The new highway interchange runs alongside a local school, and locals allege that the increased road traffic exposes children to dangerous and illegal levels of pollution. However, authorities have ignored (and suppressed) resident protests and continued construction. In Paris, as in other mega-event host cities, it is typically the poorest and most marginalized who suffer from the construction.

While these stories highlight some of the failures and oversights of the Olympics in Paris, the problem is not as straightforward as it might seem. The IOC has reformed the Olympics to better suit the host city’s development, which, in principle, means that cities no longer have to adapt to the short-term needs of the event at the expense of the long-term needs of the city. This is a step in the right direction, but it reveals pernicious problems with local politics and the complicity of local authorities in harming their own people. Local officials’ unwillingness to respond to the concerns of residents, as exemplified by the problems arising in the nine-three, only exacerbates the detrimental effects of hosting the Olympics. Thus, external forces are not the only parties to blame for harmful outcomes, as local government should also be held responsible.

In line with the IOC reforms, the plans for the Paris Olympics were blended with development plans for Grand Paris, which seeks to interlink and transform the regions surrounding the French capital. This master plan for the entire Paris metropolitan region sought to harmonize urban and economic development, modernize the area, and reinscribe it as a global powerhouse. From a distance, these processes of Olympic reform appear successful, as construction projects related to Paris 2024 were incorporated into the capital’s overall development plan. But as the struggles within the nine-three show, a view from the ground focusing on the most marginalized areas of Paris reveals a different story.

Suggestions for Authentic Reform

The Paris Olympics were less damaging to local populations than many previous Games, but this does not mean that they were faultless. These Games have made important progress in using existing structures for the sporting events. However, mega-event organizers and authorities trumpeting problem-free development and a promised legacy of social, economic, and ecological sustainability should always be questioned. Every mega-event should be investigated transparently by an independent body that has both access and enforcement powers.

Neither host city authorities nor the IOC are appropriate for this task, as both have vested interests in portraying developments as more sustainable and less damaging. Instead, this independent body should be appointed and staffed by personnel without ties to any organizational aspect of the Games. They should be empowered to investigate all aspects of planning and organization, shining a light on these notoriously opaque processes, and should operate transparently. Further, enforcement should follow infractions by organizers. Currently, however, nothing similar is close to fruition.

The damages that persist in Paris 2024 largely result from the paternalistic politics seen in the IOC and France (and in many other countries with democratic deficits). In Paris, as elsewhere, authorities often do not sufficiently account for the voices of affected residents and adopt an attitude of superiority toward marginalized and minority residents. These tendencies are augmented by the power and pressures of mega-event hosting, and, unfortunately, Paris 2024 is no exception.

Authentic sustainability should begin with accounting for the risks, costs, and benefits of hosting and follow a system where affected residents have veto power. Mega-events have the potential to bring together hearts around the globe. However, instead of glittering “Potemkin promises,” residents should be informed of the potential costs of hosting the Olympics. Too often, marginalized populations lose their voice when billion-dollar projects are in motion. Giving vulnerable communities veto power over mega-events would reshape the Olympic juggernaut entirely.

. . .

Dr. Sven Daniel Wolfe is a Swiss National Science Foundation Ambizione Fellow in the Spatial Development and Urban Policy group (SPUR) at the ETH Zurich, Switzerland. He researches the (geo)politics and (un)sustainability of mega-events.

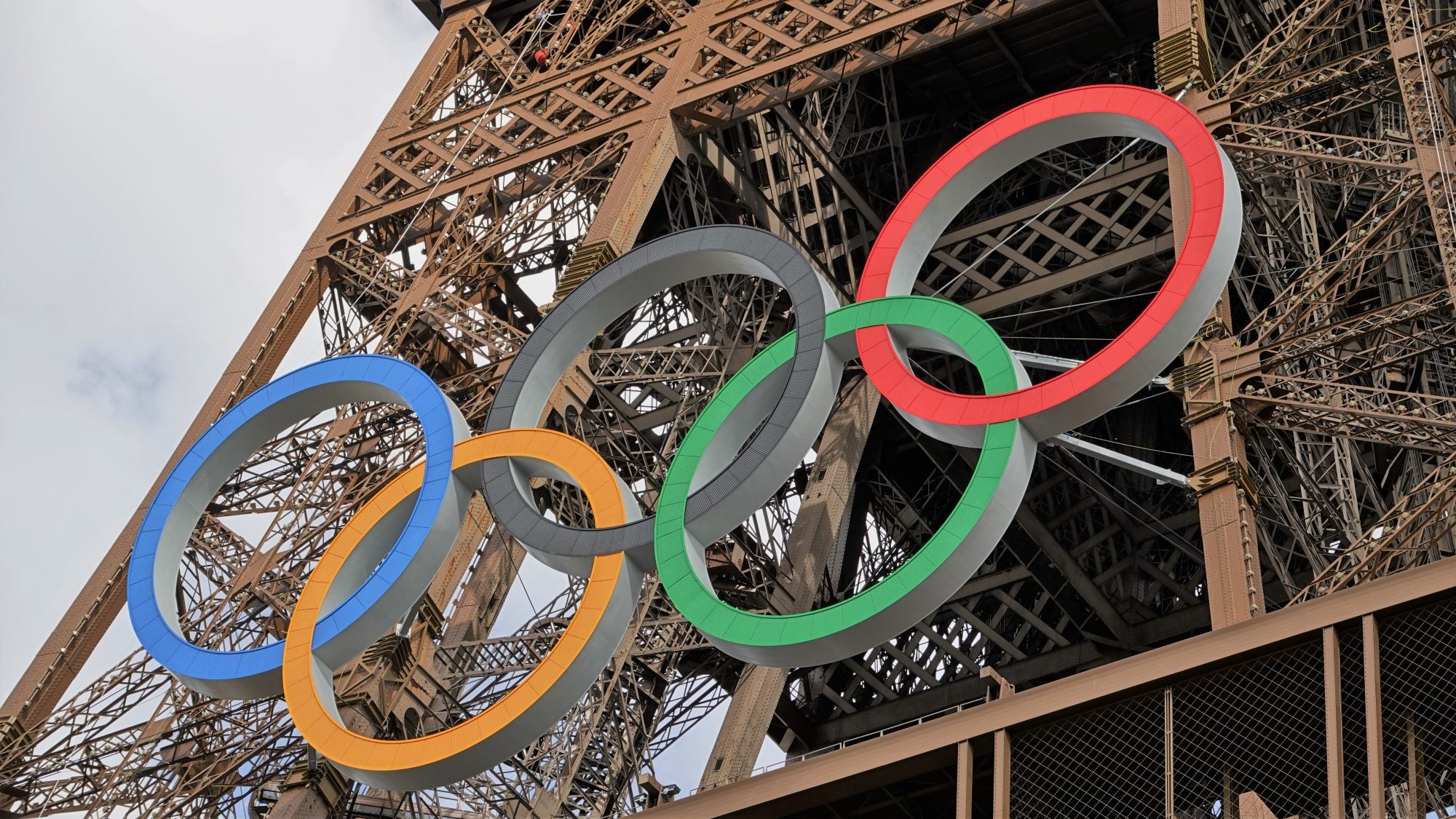

Image Credit: Ibex73, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Recommended Articles

The Maijuna-Kichwa Regional Conservation Area (MKRCA), collaboratively managed by local Indigenous communities in the Peruvian Amazon, exemplifies conservation success. However, the area is under threat by a proposed highway development…

Southeast Asia’s rich cultural diversity forms the foundation of its thriving tourism industry, which has evolved under various governance models. While national policies and market-driven urban tourism often…

In the aftermath of the 2023 Hamas attack on Israel, Israeli officials and media have frequently deployed Holocaust analogies and rhetoric to describe the depth of suffering experienced on October…