Title: Beyond Financing: Sectoral-Complementary Foreign Direct Investment and Development in Latin America and the Caribbean

The COVID-19 pandemic has adversely impacted Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), with the region facing significant economic challenges due to the loss of physical and human capital. Alongside robust macroeconomic policies, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) can play a crucial role in bridging public investment gaps and supporting long-term economic recovery and development. As such, Chinese investment in LAC, driven by mutual economic interests and by its need to relocate capital away from sectors with domestic overcapacity, stands to benefit LAC in addressing the region’s investment gaps.

Public investment gaps pose challenges to economic development in LAC

The COVID-19 crisis has taken a toll on lives and livelihoods in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), incurring a loss of physical and human capital that will hinder long-term growth. Poverty rates in the region, excluding Brazil, rose from 24 to 26.7 percent (the highest increase in decades), students lost between one and one-and-a-half years of education, and the fall in the UN Human Development Index in this period dwarfed even the drop that occurred during the 2008 global financial crisis. Moreover, economic downturns have historically harmed productivity in the region, pointing to potentially major scars from the pandemic. In fact, LAC’s productivity underperformance is widespread, cutting across sectors and types of firms. The medium-term growth outlook for the region remains subdued, and real output will not return to the five-year pre-pandemic path the IMF envisaged in 2021.

Since public investment drives economic growth and poverty reduction, immediate policies that promote public investment are warranted to boost productivity growth and accelerate economic development to bolster the pandemic recovery. Education, health, and infrastructure—sectors traditionally reliant on public investment—generate positive spillovers to other industries, improving the human capital of the entire economy and thus benefiting long-term growth. However, LAC countries face large public financing gaps that constrain their economic development. A 2019 study by Castellani et al. shows that over the last few decades, LAC countries have lost significant ground vis-à-vis Asian emerging markets in the quality and quantity of infrastructure. LAC’s investment gap, or the difference between actual investment and the optimal level that maximizes social welfare, was above 3 percent of GDP in 2015 and is expected to reach 4.4 percent in 2030. When factoring in the public investment needed to eradicate extreme poverty as outlined by the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the funding gap will reach 7.0 percent of GDP, or $798 billion, by 2030. In short, the growth challenges of Latin American economies, exacerbated by the pandemic, could be followed by another “lost decade”—a period in the 1980s when many indebted LAC countries missed the opportunity to fund critical infrastructure that could unleash the region’s growth potential.

Can FDI fill the public investment gap?

The recent history of public financing gaps in the region raises a natural question for development: can foreign direct investment (FDI), a type of private investment that intends to establish lasting interests in the recipient country, fill the public investment gap in LAC? Investment and savings are lower in LAC countries than in the rest of the world, and the saving gap is larger than the Emerging Market Economy (EME) average. Traditionally, international capital markets offset these saving deficits, including during the pandemic in 2021 and early 2022. However, the external financing conditions for LAC economies have quickly become unfavorable since 2022, when major central banks began hiking interest rates drastically to combat soaring inflation, increasing the borrowing costs of investment in LAC. Net capital inflows into the region have weakened, driven by a sharp decline in portfolio inflows (i.e. cross-border investment in debt and equity instruments), halting LAC’s nascent economic recovery.

Nevertheless, FDI inflows have remained resilient in LAC in contrast to the steep decline of FDI in advanced economies (AEs) and EMEs, indicating that international investors remain confident in the region’s long-term growth prospects. Asian FDI in LAC has been increasing steadily and accounted for 31 percent of LAC’s FDI stock in 2019, with most investment projects sourced from China, Japan, and India. These resilient FDI inflows have created hope that FDI could help partially fill the public investment gap in LAC.

In particular, the electricity generation and distribution sector in Latin America and the Caribbean has become a major target of Chinese investment, with more than a dozen acquisition deals of over $1 billion on average across the region. In October 2019, the State Grid Company of China purchased Chilquinta Energia, the third-largest electricity distributor in Chile, for $3 billion. Two months later, China Yangtze Power International acquired Luz del Sur, the largest electricity company in Peru, for $3.6 billion. Both acquisitions were among the largest FDI ever received by Chile and Peru, bringing new capital to the underinvested utility sector in these countries.

Fear of FDI?

The recent trends of China’s overseas investment feature sectoral complementarity, in which China’s advantage in the utility and manufacturing sectors complements weaknesses in the same sectors in LAC. The recent overseas investment from China mainly targets LAC’s manufacturing and utility sectors, where China has a distinct advantage. This investment is driven by mutual market interest and investment opportunities in sectors traditionally neglected in LAC. As a result, Chinese FDI has successfully filled the public investment gap in LAC, generating improvements in infrastructure that benefit the region’s economic landscape.

Sectoral complementarity should ease excessive concerns regarding China’s geopolitical motivations. While China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is expected to deliver trillions of dollars to the infrastructure sector in developing countries, some argue that BRI would induce recipient countries to build excessive debt to China and hence fall into China’s “debt trap.” On the contrary, the latest research shows that regardless of political motivations, mutual economic interests drive China’s overseas investment in LAC.

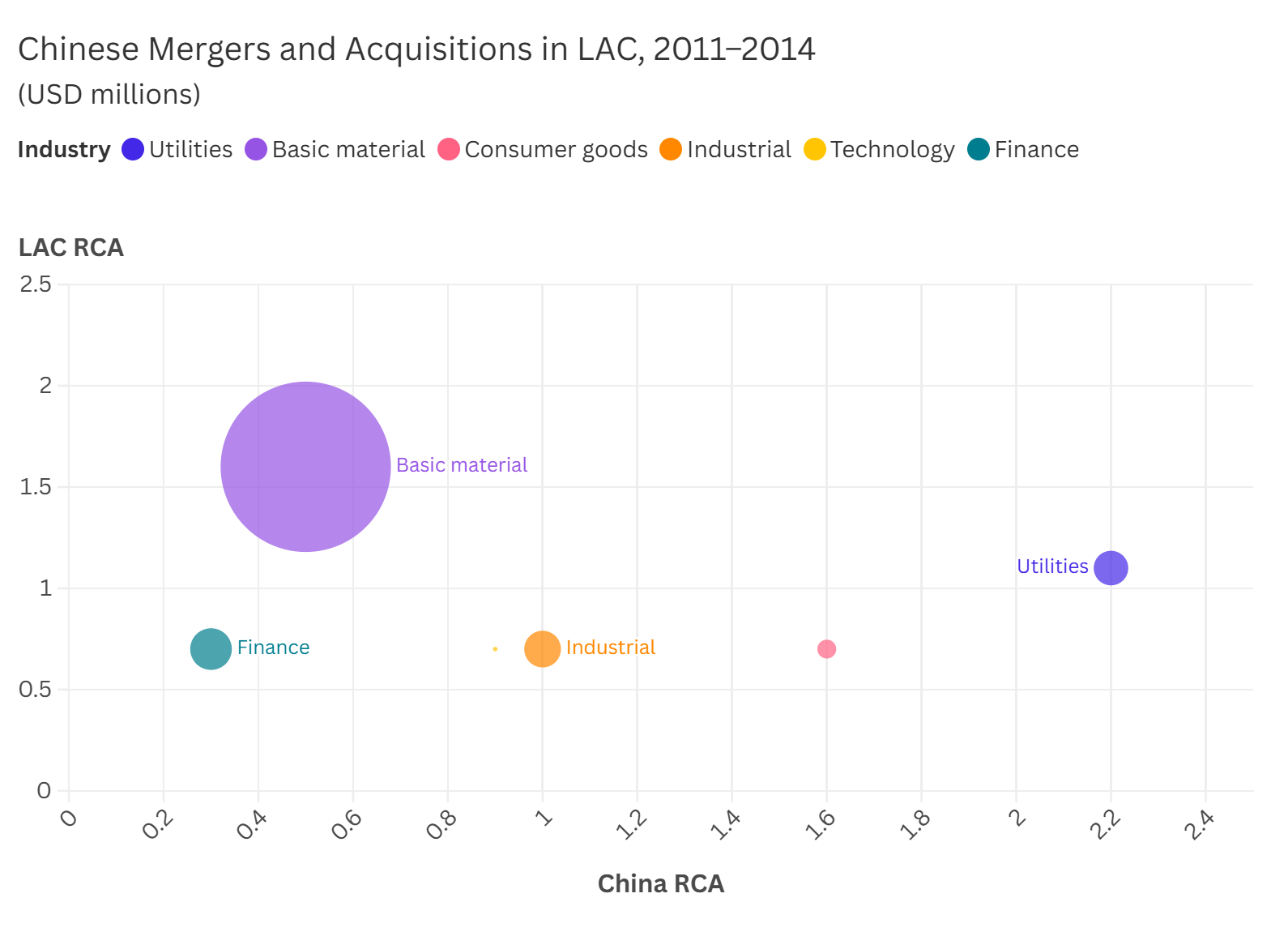

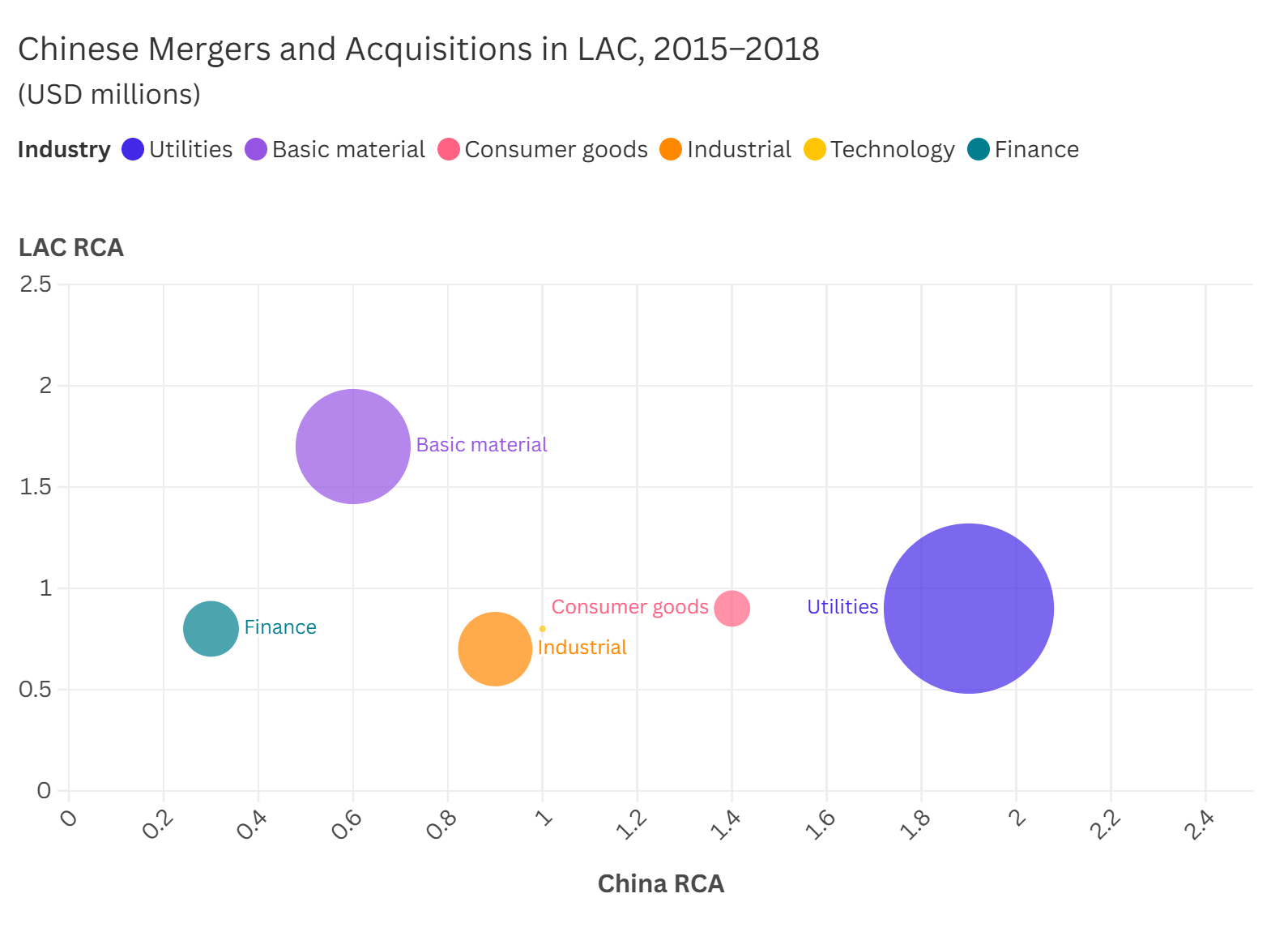

A 2021 study by Ding et al. quantitatively demonstrated that the rising volume and changing composition of Chinese investment in LAC can be associated with the sectoral complementarity between China and LAC—a pattern that has also been observed in the FDI patterns of major advanced economies. Using the revealed comparative advantage (RCA) index, which measures a country’s competitiveness in different sectors, the authors find that Chinese FDI measured by merger and acquisition value from 2011 to 2014 was concentrated, both overall and in LAC, in the basic materials and energy sectors, where China had low RCA. However, from 2015 to 2018, China increased its mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in sectors where China has relatively high RCA, such as consumer goods, telecommunication services, and, particularly, utilities (where LAC has low RCA). In other words, China’s FDI has shifted from compensating for its lack of resources to leveraging its strength in building infrastructure.

Source: Ding et al. (2021).

Note: the size of the bubble indicates the total value of M&A in the sector.

Moreover, this sectoral complementarity can be linked to China’s ongoing efforts to reduce domestic excess capacity as its economy rebalances from investment and manufacturing-driven growth to consumption and services-driven growth. In fact, China’s 2015 Supply-Side Structural Reforms emphasize capacity reduction to guide the transition of the Chinese economy to a “new normal.” Because domestic excess capacity has affected profitability and growth prospects in China, a shift toward overseas markets for investment opportunities has become a natural choice for Chinese corporations. Overseas investment is particularly important for China’s large state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which must expand assets while supporting national development strategies such as capacity reduction and the BRI.

Policy recommendations

The COVID-19 pandemic’s lasting impacts on global value chains and FDI flows pose both challenges and opportunities for LAC to attract FDI. Given China’s changing overseas investment behavior, LAC has the potential to exploit the complementarity in sectors where China demonstrates comparative advantage, like consumer goods and telecom services. For example, China added the Digital Silk Road (DSR) to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2015, creating a platform that provides cutting-edge, cost-effective telecommunications equipment to the global community. By embracing Chinese FDI in the telecoms industry, LAC could capitalize on the advantages of digitalization, fostering long-term productivity gains and strengthening economic connections between the two regions. Essentially, to attract and maximize FDI benefits from China, LAC should focus on sectors where China has a comparative advantage.

To the extent that Chinese investment is also driven by its need to relocate capital away from sectors with domestic overcapacity (e.g. manufacturing and utilities), policies to attract FDI will enable LAC to benefit from Chinese investment to address its own investment gaps in infrastructure and consumer products. Easing capital flow management measures, streamlining facilitating trade and FDI process, offering tax incentives targeting high-tech companies or industries, and deepening financial markets could generally attract foreign investors to invest in underdeveloped sectors in LAC. A stable macroeconomic environment, favorable growth outlooks, and strong institutional frameworks are also important pull factors of foreign investment. Policies to streamline trade and investment processes can also attract more foreign investors.

In addition to reaping the benefits from FDI inflows, LAC economies will need to build sound macroeconomic policies to address structural challenges, including healing the scars of human and physical capital loss during the pandemic. Fiscal policy should allocate sufficient resources for health spending, including vaccination, and continue to support households and firms in a more targeted fashion while the pandemic persists, backed by credible assurances of medium-term debt sustainability to maintain access to finance. Monetary policy has started to address inflationary pressures but should continue to support economic activity insofar as the dynamics of inflation expectations permit. Furthermore, LAC’s financial policy should shift from blanket support to targeted support of viable firms to ensure that necessary labor and capital reallocations are not hindered. Supply-side policies should foster inclusive growth, including through progressive and growth-friendly tax reforms and measures to intensify climate change adaptation and mitigation. Ultimately, structural reforms and attracting FDI in underdeveloped domestic sectors—including those from China driven by mutual economic interests—will build macroeconomic resilience and unlock LAC’s growth potential.

. . .

Yue Zhou is an economist in the Asia Pacific Department at the IMF. He has extensive experience in IMF lending operations and surveillance, including advising country authorities on macroeconomic policy reforms and providing technical assistance to client countries. Prior to joining the Fund, he was a consultant in the South Asia Chief Economist Office at the World Bank. He has published on issues related to international finance, public finance, macroeconomics, and development. He holds a Ph.D. in International Economics from the Graduate Institute Geneva, and a master’s and bachelor’s from Peking University.

Image credit: Josue Isai Ramos Figueroa, Unsplash, via Unsplash Content License.

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…