Title: Re-thinking the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy: A Bottom-up Approach

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from a recent multinational study with key foreign policymaking personnel in eight Indo-Pacific countries reveal how the EU has failed to solidify its relevance and credibility in the Indo-Pacific. As a result, the EU must drastically transform its strategy by shelving its hitherto top-down approach for a more bottom-up one.

Introduction

In April 2021, the European Union released the “EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific,” a roughly 8,000-word document that details the EU’s intention to prioritize involvement in the Indo-Pacific in its foreign policy. The EU identified seven priority areas for engagement, ranging from green energy transition to security and defense. The EU identified the Indo-Pacific as an essential component of the EU’s overarching aim of playing a “more active role” in international relations to assert its global influence. Indo-Pacific countries are important trading partners for the EU—especially China, Japan, South Korea, and India— and as a whole, 25 percent of total EU exports go to the Indo-Pacific (37 percent of total imports). The EU, by volume, has roughly the same amount of two-way trade as the United States in the Indo-Pacific. Therefore, the EU has significant interests but also economic levers it can use in the Indo-Pacific.

However, in the more than four years since the release of the strategy, the EU’s Indo-Pacific efforts have fallen short of expectations. To assess the EU’s performance, research funded as part of an EU Jean Monnet Network Grant was undertaken in eight Indo-Pacific countries: Australia, China, India, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Thailand, and Taiwan. During this study, a team of more than 40 experts from 27 partner universities conducted more than 100 interviews between 2023 and 2024 with key personnel involved in the foreign policymaking of these countries to ascertain their opinions of the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy.

Interviews covered six standard questions, starting with a broad question about the EU as an international actor and then narrowing to specific questions about the importance of the EU bilaterally and to the Indo-Pacific, the EU’s seven Indo-Pacific priority areas, and the future trajectory of the EU (both bilaterally and in the Indo-Pacific). Lastly, the researchers asked a question about the impact of the war in Ukraine on the EU’s Indo-Pacific ambitions. Although the research produced a significant amount of data, one of the consistent points of discussion across all countries was the topic of whether the EU should have an overarching Indo-Pacific strategy or not.

Overview of the Research

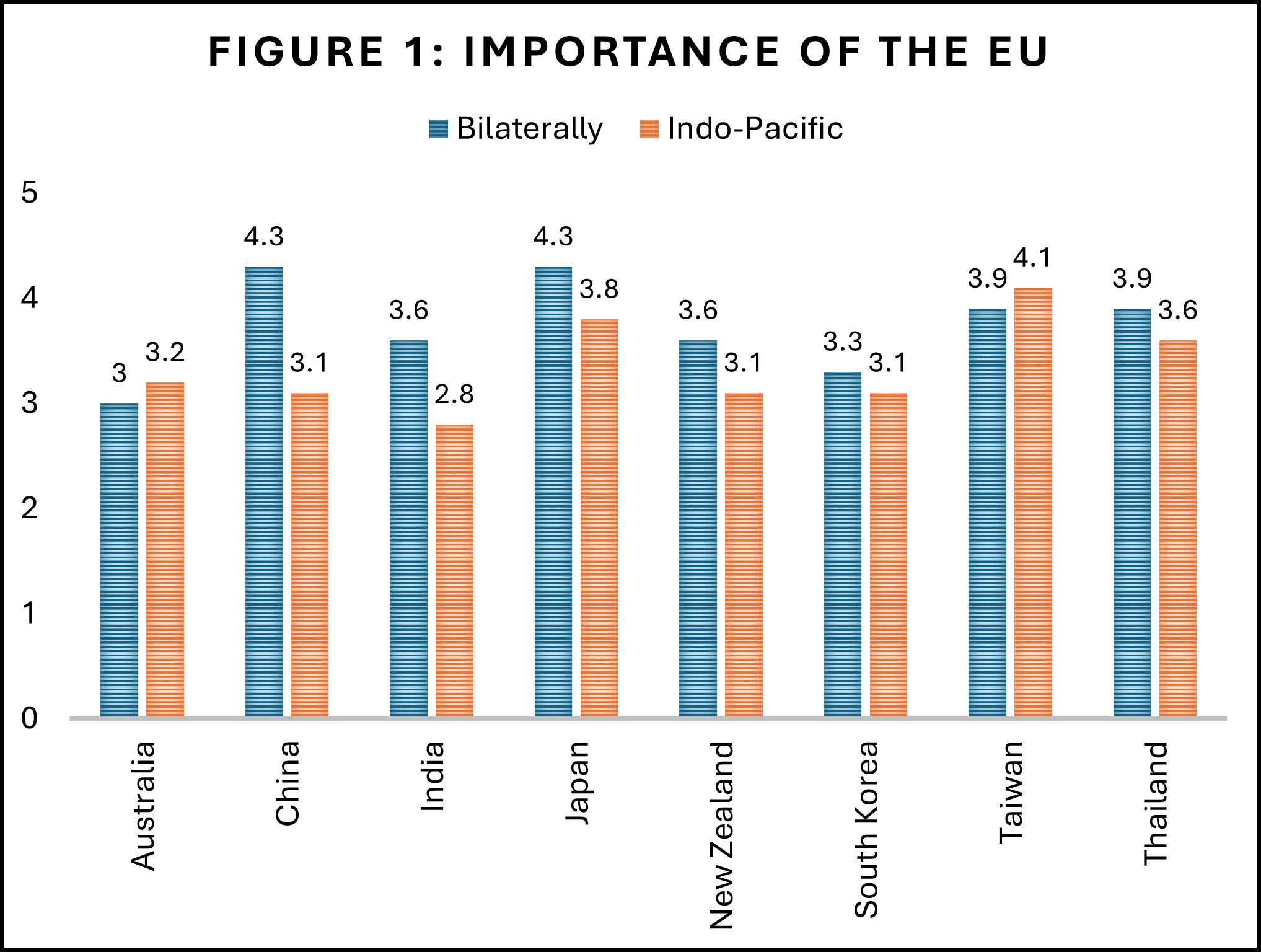

In the initial phase of the interviews, key informants were asked to judge the importance of the EU to their country and the Indo-Pacific more broadly (1 being not important, 5 being extremely important). Across all the Indo-Pacific countries, all interviewees judged the EU to be somewhat important, both to the country in question and to the Indo-Pacific. The widespread perception of the EU’s importance among Indo-Pacific countries indicates that it is performing well in its bilateral relationships.

Regarding the importance of the EU to the broader Indo-Pacific region, key informants generally rated it as less significant than in bilateral contexts. Only Australia and Taiwan assigned higher scores to the EU’s role in the Indo-Pacific overall than they did for their bilateral relationships. In particular, Taiwanese key informants judged the EU as being highly important due to perceived alignment on issues such as semiconductor supply chains and a desire for a green energy transition. In contrast, Indian key informants were the most skeptical, citing the EU’s limited foreign policy capabilities—such as its lack of legal competence in this area—and a perceived lack of internal unity as constraints on its regional influence.

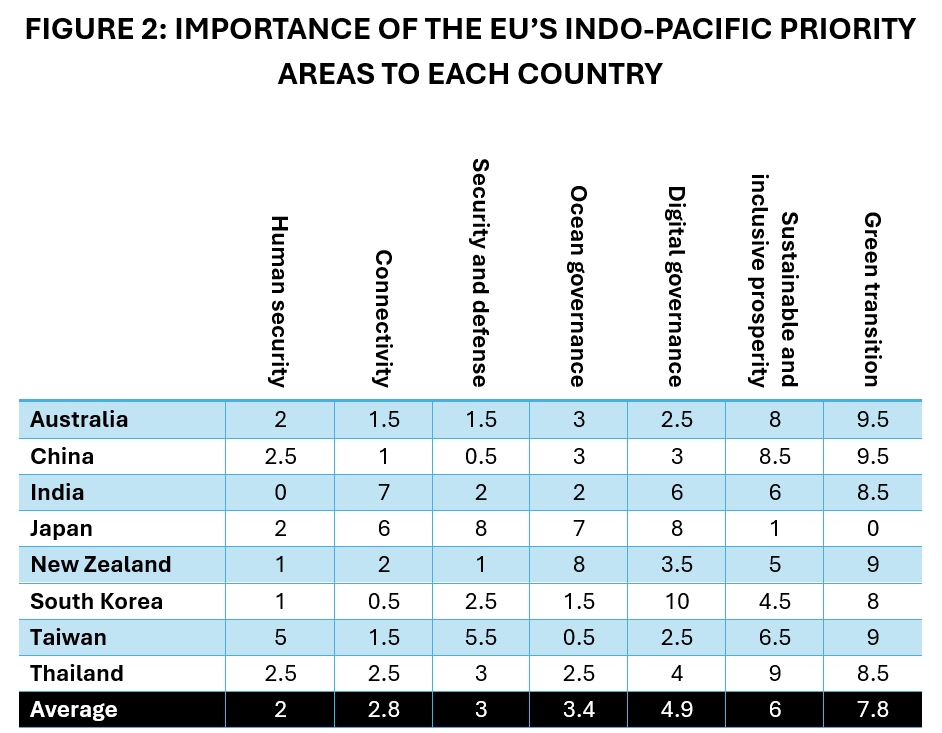

Key informants were then asked to comment on the importance of each of the EU’s seven priority areas of its Indo-Pacific Strategy to their country. Using a scale of 0 being irrelevant and 10 being crucial, the data demonstrated that there is significant diversity of opinion across the Indo-Pacific. Green transition scored the highest in terms of importance—except for Japan, where it only scored a zero—and was deemed an area where the EU could have a significant impact. The priority areas of sustainable and inclusive prosperity, digital governance, and ocean governance (in descending importance) were deemed very important to some countries while less so to others. Security and defense were easily the most talked about priority area in the interviews due to the rising geopolitical tension in the Indo-Pacific. Japan and, to a lesser extent Taiwan, were the only countries that saw the EU as having a role while others were far less optimistic. A common attitude expressed across all the countries (even in the majority of the countries where it was deemed a 3 in importance) was that, while the EU had the potential to make an impact in security and defense, its efforts to have an impact in this area would continue to be inhibited by the need for unanimity amongst all 27 member states when making critical foreign policy decisions. Whether the EU could gain the necessary strategic autonomy to become a more relevant Indo-Pacific actor in security and defense was quite polarizing, with optimistic and pessimistic camps identifiable in the data.

Analysis

The results unequivocally demonstrate that the Indo-Pacific is a heterogeneous region, both in terms of how different Indo-Pacific countries view the EU and also in terms of what they see as the most pressing issues they are facing. Indeed, as another analysis from this project has argued, characterizing the Indo-Pacific as a region or super region is a mistake because the sheer geographical size of the Indo-Pacific, which, at its largest definition, stretches from the east coast of Africa to the west coast of the Americas. Rather, it is better thought of as a constellation of different regions, each with its own unique geopolitical dynamics. Consequently, designing and implementing an effective Indo-Pacific strategy is a tall order for any actor, let alone an actor like the EU that already faces serious limitations in its ability to produce coherent and effective foreign policies.

The discourse underpinning the Indo-Pacific is heavily securitized due to the perceived threats emanating from the rise of China and, therefore, much of the attention concerns security and defense and ocean governance—areas in which the EU is generally not regarded as a relevant or capable actor. Most of the Indo-Pacific countries examined cannot conceive of the EU as a strategic or geopolitical player, primarily because it lacks sovereign statehood and the associated tools of hard power. Instead, the EU is perceived as a “civilian” power, effective only in areas of “low politics,” or “secondary non-security issues such as economic policy and social policy.” As a result, although one of the driving aims for releasing the 2021 Indo-Pacific Strategy was to gain legitimacy as a geopolitical actor, this vision is not necessarily shared by Indo-Pacific countries.

However, the EU has still made strides with its policy in the Indo-Pacific. Viewed as a leader of climate action, the EU’s green transition agenda was the most positively rated of the seven priority areas. This is likely tied to the fact that since the release of its Indo-Pacific strategy, the EU has established “green alliances” with Japan, Korea, and the Pacific Islands countries to strengthen bilateral cooperation on climate action.

Furthermore, the EU is an attractive economic player in the Indo-Pacific, as it has Free Trade Agreements with Japan, Vietnam, New Zealand, and South Korea and is in negotiations with India, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines. There has also been some initial discussion on the EU joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). In addition, the EU is the world’s largest donor of Official Development Assistance (ODA) and provides significant assistance to developing countries in the Indo-Pacific. Lastly, the EU is emerging as a relevant digital player in the Indo-Pacific, especially due to the growing concerns in Indo-Pacific countries about Sino-American technological rivalry.

At a time when the geopolitical dynamics of the Indo-Pacific are escalating due to growing enmity between the United States and China, the EU distinguishes itself as an alternative actor due to its non-sovereign status and limited military capacity. Consequently, the EU is often seen as a partner capable of fostering more positive, less zero-sum, interactions. This perception offers the EU a useful platform from which to build its Indo-Pacific ambitions. However, given the heterogeneity of the Indo-Pacific geopolitical space and the EU’s ongoing struggle to establish its geopolitical relevance, the EU should consider abandoning its top-down, “macro” Indo-Pacific strategy for a more bottom-up approach.

Conclusion

Ultimately, more than four years after the release of the EU’s Indo-Pacific strategy, it is time for the EU to rethink how it can better fulfill its aim of becoming a more relevant Indo-Pacific actor. A first step would be to abandon the hitherto top-down approach and adopt a bottom-up approach. The ineffectiveness of the EU’s top-down Indo-Pacific strategy was highlighted in the interview data, as the majority of the key informants were not cognizant that the EU had an Indo-Pacific Strategy at all, let alone specific priority areas. A bottom-up approach would entail the EU building on its relatively strong bilateral relationships with individual Indo-Pacific countries, focusing firstly on the priority areas that matter most to those countries. Over time, the EU could work on fostering more cooperation in areas where the EU is deemed less credible, such as security and defense. In cases where there is significant overlap in priorities amongst different countries, the EU could work to link these countries together as multilateral agreements and initiatives. A bottom-up approach like this could organically grow into something akin to a de facto Indo-Pacific strategy, albeit without the overarching strategic documentation and framework.

While not having an explicit Indo-Pacific Strategy might be seen in Brussels as hurting the EU’s attempt for relevance in this geopolitical space, continuing to pursue this current pathway undermines what is unique and respected about the EU in the region—that it is not a typical global power and can be a reliable partner in a number of important, non-traditional areas.

. . .

Nicholas Ross Smith is a Senior Research Fellow at the University of Canterbury’s National Centre for Research on Europe and the academic lead of the Jean Monnet Network: ‘EU in the Indo-Pacific’ (EUIP). His research coalesces around the regional implications of great-power rivalry and how relatively smaller states seek to navigate changing geopolitical environments. He is the author of two books and more than two dozen peer-reviewed journal articles, including articles in International Affairs, The Journal of Politics, and Review of International Studies.

Disclaimer: This research was funded by the European Union’s Erasmus+ scheme. The views and opinions expressed are however those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union.

Image Credit: Wu Yi, Unsplash Content License, via Unsplash.

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

Foreign employers have the potential to influence cultural norms and improve female employment outcomes in regions with historically low female labor force participation (FLFP), such as the Middle…