Title: Powering the Periphery: Rethinking Rural Electrification in Fiji

Fiji, a Pacific Small Island Developing State (PSIDS), faces rural electrification challenges due to its dispersed geography and climate vulnerabilities. With 6 percent of Fijian rural households lacking electricity, the government employs grid-extensions and off-grid solutions, including solar home systems (SHS), solar mini-grids, and micro-hydro systems. However, challenges exist in sustaining these off-grid projects. Empowering local communities, incentivizing private energy service companies (ESCOs) to serve remote areas, and fostering enhanced public-private collaboration are essential strategies for delivering reliable, sustainable, and clean electricity to Fiji’s underserved rural populations.

Introduction

With its more than 300 scattered islands and population of under a million, Fiji confronts a challenge common to PSIDS: pursuing economic development and meeting increasing energy demand in rural communities, all the while mitigating the adverse impacts of climate change.

Despite its minimal contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions, Fiji has demonstrated strong climate leadership by committing to a 30 percent reduction in emissions by 2030 in adherence to the Paris Agreement. The archipelago also aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. Central to this commitment is the transition to 100 percent renewable energy for electricity generation.

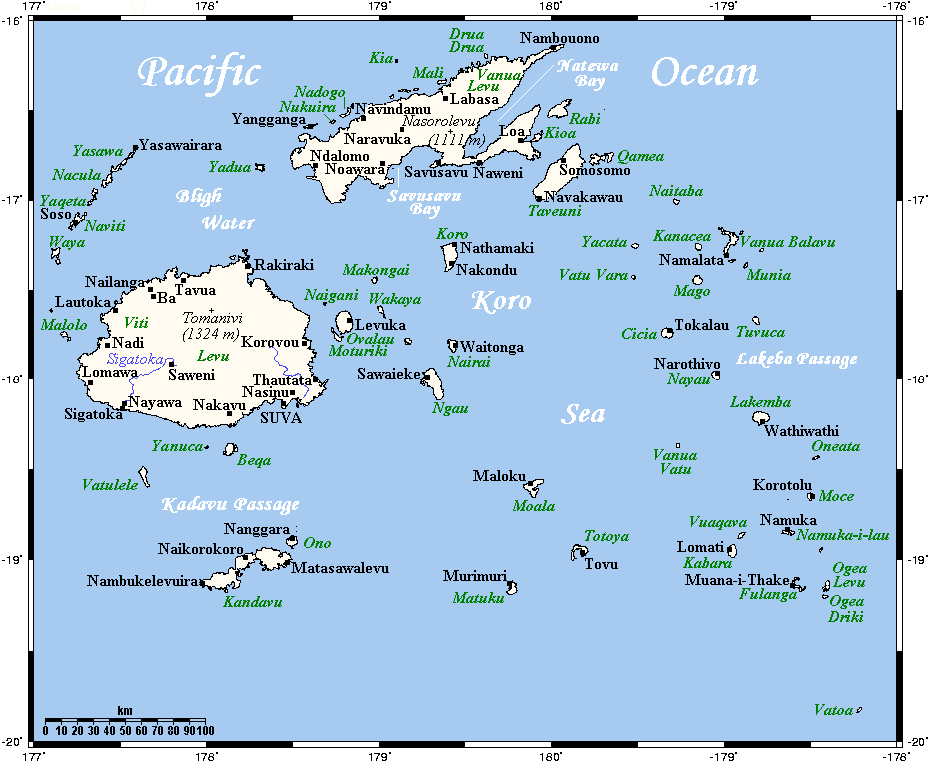

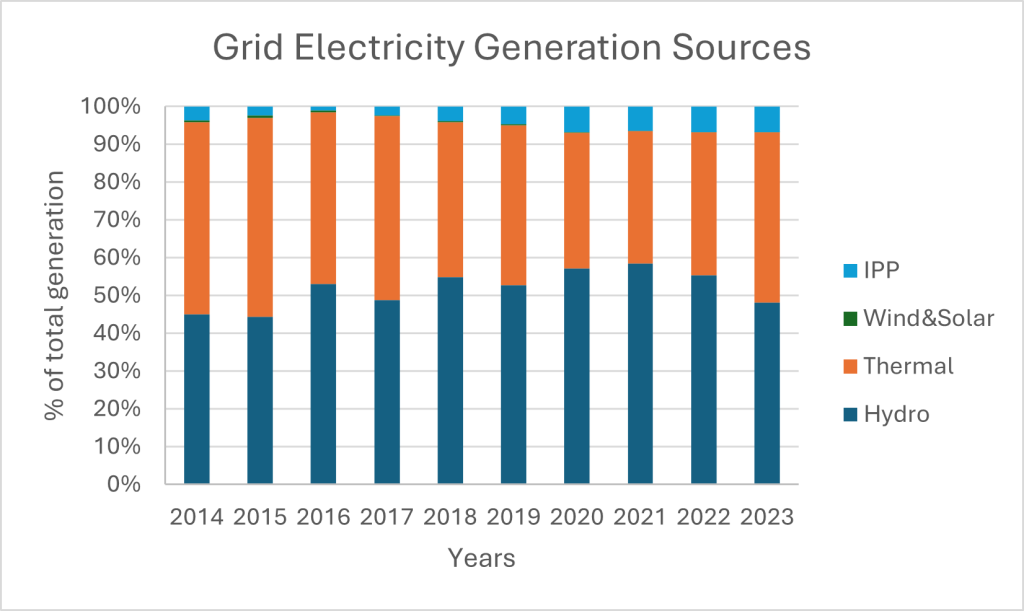

Due to Fiji’s dispersed island geography (Figure 1), electricity is provided through both grid—which is supplied through Energy Fiji Limited (EFL) to four islands—and off-grid systems—which generate energy at civilian sites and are not connected to the main grid.[1] Due to a lack of data on the exact amount of off-grid generation, it is difficult to accurately assess Fiji’s off-grid energy progress. For Fiji’s grid electricity generation, EFL provides data on its generation (Figure 2). As of 2023, 56.5 percent is sourced from renewable energy, including hydropower, biomass, and wind, while the remaining 43.5 percent is generated from heavy fuel oil and industrial diesel oil.

Fiji’s Current Status of Electricity Access

According to 2017 census data from the Fiji Bureau of Statistics (FBoS), 3.7 percent of Fijian households lack electricity, a disproportionate number of which are in rural areas. As seen in Figure 3, rural areas have the highest share of SHS, village diesel-powered plants, and generators. While SHS and diesel generators provide basic power in many rural communities, their limited capacities highlight the need for more reliable and higher-tiered electricity access. Electricity access is often classified using a tier system, which measures access based on factors like availability, reliability, affordability, and quality, ranging from Tier 0 (no access) to Tier 5 (highest-quality access). Moreover, an additional 15.6 percent of households (30 percent rural and 4 percent urban households) require enhanced electricity services beyond basic lighting.

| Percentage of households | |||

| Sources of Electricity | Urban | Rural | Total |

| Grid electricity | 92.9% | 60.3% | 78.5% |

| FSC electricity | 0.2% | 0.03% | 0.1% |

| Vatukoula Goldmine electricity | 0.4% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| Village diesel plant | 0.01% | 3.4% | 1.5% |

| Village hydro plant | 0.002% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| Own generator (diesel) | 0.5% | 3.1% | 1.6% |

| Solar (mostly SHS) | 3.4% | 23.9% | 12.5% |

| None | 1.9% | 6.1% | 3.7% |

| Other (specify) | 0.8% | 2.7% | 1.7% |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Figure 3: Percentage of households in Fiji utilizing different sources of electricity. Source: Fiji Bureau of Statistics

Fiji’s Key Policies and Programs Related to Rural Electrification

Guided by the Climate Change Act 2021, Fiji’s National Development Plan (2025-2029) (NDP) acknowledges the disparities between rural and urban areas in terms of poverty levels and access to basic services like educational and healthcare facilities and transportation. The NDP aims to make electricity accessible to 93 percent of the rural population by 2029, as access currently only reaches 86.7 percent of residents.[2] While the NDP prioritizes rural and outer island development, it lacks a clear definition of what “electricity access” entails because it fails to specify tier levels, hindering targeted interventions and leading to a disparity between urban and rural areas in terms of the level of energy services people enjoy. This oversight could make it challenging to attract investments to provide higher-tiered energy access to marginalized communities.

The Fijian government’s rural electrification efforts are guided by the 2022 Electricity Policy (EP) and the 2023-2030 National Energy Policy (NEP). These policies prioritize the decentralization of energy access by encouraging the use of off-grid solutions.

To finance off-grid solutions, the Fijian government, in its 2024-2025 budget, has allocated a combined FJ16.8 million (USD 7.4 million) for subsidizing SHS and electricity access for poor households, wiring households to newly extended electrical grids, and grid extensions on two Fijian islands.

Current Programs and Projects on Rural Electrification

The Fiji Department of Energy’s (FDoE) Rural Electrification Unit spearheads rural electrification efforts by deploying SHS, micro-hydropower systems—designed to power a small village—solar mini-grids, and biofuel generators. Yet, FDoE’s progress in electrification of remote villages has been slow, largely due to insufficient access to financing and challenges with sustainable operations and maintenance.

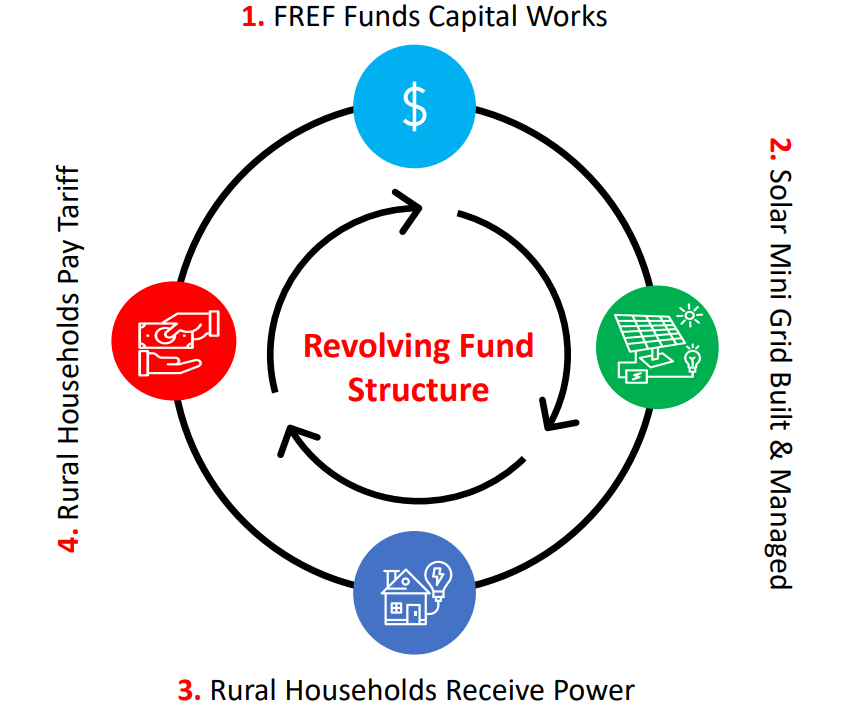

The 2017 Fiji Renewable Energy Fund (FREF) addresses these challenges through blended finance which, attracts private sector investment. Supported by financial backing from various international partners (including the UN Development Programme (UNDP) and Asian Development Bank), the FREF aims to develop mini-grids to provide clean, affordable, and reliable renewable energy to rural communities through a revolving fund structure (Figure 4). While local communities pay relatively low tariffs, the cost is still higher for small outer island communities than on the mainland.

The recent launch of the UNDP-FREF Support Project in January 2025 will electrify three rural Fijian island villages using solar mini-grids, benefiting 1,031 Fijians. Following the current rate of progress, another 17 rural maritime villages will be electrified over the next 18 months.

Challenges in Electricity Access

With approximately 100 inhabited islands, Fiji faces significant challenges in extending grid electricity to its entire population. Consequently, off-grid electricity plays a key role in providing access to these communities, which primarily depend on farming or fishing for their livelihoods. Access to higher-tier electricity would mean that communities would transition towards greater productivity. For instance, renewable energy based mini-grids in rural or smaller outer maritime communities would ensure the operation of freezers where fishing communities could store their catch and then later sell it in markets on the mainland. For farming communities, a solar-powered water irrigation system would reduce the operational cost of gasoline or diesel powered water pumps. Similar situations exist in other PSIDS where rural populations heavily rely on fishing and, where feasible, agriculture.

Fiji’s electricity access is further challenged by its infrastructure’s physical vulnerability to natural forces, creating additional financial burdens on an already strained system. The frequent occurrence of severe weather events, exacerbated by climate change, damages existing energy infrastructure, leading to power outages requiring costly repairs. Moreover, the high cost of fossil fuels coupled with the capital-intensive nature of renewable energy installations creates significant financial hurdles. Rural communities, often lacking access to credit and facing unstable incomes, struggle to afford reliable energy services and the maintenance of off-grid systems. This financial strain, alongside the technical complexity of maintaining decentralized energy solutions, perpetuates inequality in energy access across the islands.

Policy Recommendations to Improve Rural Electrification

To guarantee the longevity and effectiveness of electrification initiatives by development partners and the Fijian government—but also to prepare community members to support these projects—Fiji should expand the decision-making power of impacted communities in policymaking. Stakeholder involvement in projects from the planning stages ensures they can provide input that tailors projects to their needs, supports their culture, and delivers socio-economic benefits.

Furthermore, communities should have access to better methods of sustainable income generation. Given the financial constraints faced by rural communities, the Fijian government should provide greater market access for fisheries and farms and engage with communities in discussions on furthering reliable income generation strategies.

Within the government, it is essential to increase funding for electrification policies, namely those that prioritize off-grid solutions. Past aid given to Fijian electrification projects reveals a disparity in funding: off-grid projects typically receive less support than on-grid initiatives due to their increased logistical costs. With targeted financing mechanisms, this imbalance could be fixed, establishing equitable access to electricity for all communities.

To implement rural electrification solutions that remain viable, it is also critical to empower communities with technical skills, which would necessitate training community members in the maintenance of renewable energy systems. This approach reduces reliance on external technicians, whose response times are impacted by travel and logistical challenges in remote areas. By equipping communities with the skills to address minor technical issues, disruptions to energy access can be minimized.

Finally, to enhance rural electrification in Fiji’s challenging contexts, a strategic emphasis on energy service companies (ESCOs) is paramount. Incentivizing private sector involvement through ESCOs specifically designed to serve rural areas and small outer islands requires government and donor support to offset the inherent challenges of a dispersed population and high transportation costs. Simultaneously, fostering robust communication channels between communities, ESCOs, and government agencies is essential for effective information exchange and responsive service personnel. Furthermore, strengthening multi-stakeholder collaboration with academia will maximize the impact of rural electrification initiatives, creating a coordinated approach that leverages diverse expertise and resources.

Conclusion

Rural electrification remains a priority for Fiji, as it is intrinsically linked to the nation’s socio-economic development and climate resilience. By implementing robust electrification policies and prioritizing the aforementioned community-centric recommendations, Fiji can effectively address its financial and logistical challenges. Specifically, the focus on empowering communities with technical skills and incentivizing private sector involvement through ESCOs will improve off-grid energy solutions. While the specific challenges and solutions may vary across PSIDS, governments should prioritize tailoring electrification projects to the unique needs and strengths of their communities, using Fiji’s experience as a foundational framework. Ultimately, these efforts will contribute to building resilient and sustainable energy systems across the region, fostering prosperity for all Pacific communities.

. . .

Ravita D. Prasad is an Assistant Professor in Physics at the College of Engineering, Technical Vocational Education and Training at Fiji National University. She has been teaching Physics and Sustainable Energy at the University for over 15 years. Her current research interests are low-carbon development, sustainable energy, and energy access for marginalized communities.

Image Credit: Michael Coghlan, Creative Commons, via Flickr.

[1] The sole public energy utility company in Fiji, Energy Fiji Limited (EFL), supplies this electricity to the four main islands: Viti Levu, Vanua Levu, Ovalau, and Taveuni.

[2] Please note NDP reports percent of population while, Figure 3 shows in percent of households and present 93.4 percent of rural households have electricity.

Recommended Articles

This article examines the EU’s cyber diplomacy in Moldova’s parliamentary elections from September 28, 2025, which marked a new chapter in the bloc’s cyber diplomacy. Drawing on analysis of Russian…

Export controls on AI components have become central tools in great-power technology competition, though their full potential has yet to be realized. To maintain a competitive position in…

The Trump administration should prioritize biotechnology as a strategic asset for the United States using the military strategy framework of “ends, ways, and means” because biotechnology supports critical national objectives…