Title: Bitcoin as Legal Tender in El Salvador: The First Fifty Days

On September 7, 2021, El Salvador became the first country to introduce bitcoin as legal tender after swift approval of the law only three months prior. However, Salvadoran citizens, multilateral institutions, and international capital markets have not received the news well and are concerned that the costs of this monetary experiment will exceed the potential benefits. If there are any lessons from this monetary experiment, El Salvador is a good example on how not to adopt a cryptocurrency as a legal tender. The use of digital currencies as a legal tender can only be achieved through multilateral cooperation instead of one country attempting it on its own.

On June 5, in a pre-recorded video, the president of El Salvador announced at the BITCOIN 2021 conference in Miami that El Salvador would be the first country to adopt bitcoin as a legal tender. The announcement was made without previous knowledge by El Salvadorans. By June 8, the Ministry of Economy presented a draft of the bill to the National Assembly, which approved and published it within a day—an easy feat as the executive’s party holds a super majority in the legislature. Bitcoin became legal tender on September 7, 2021.

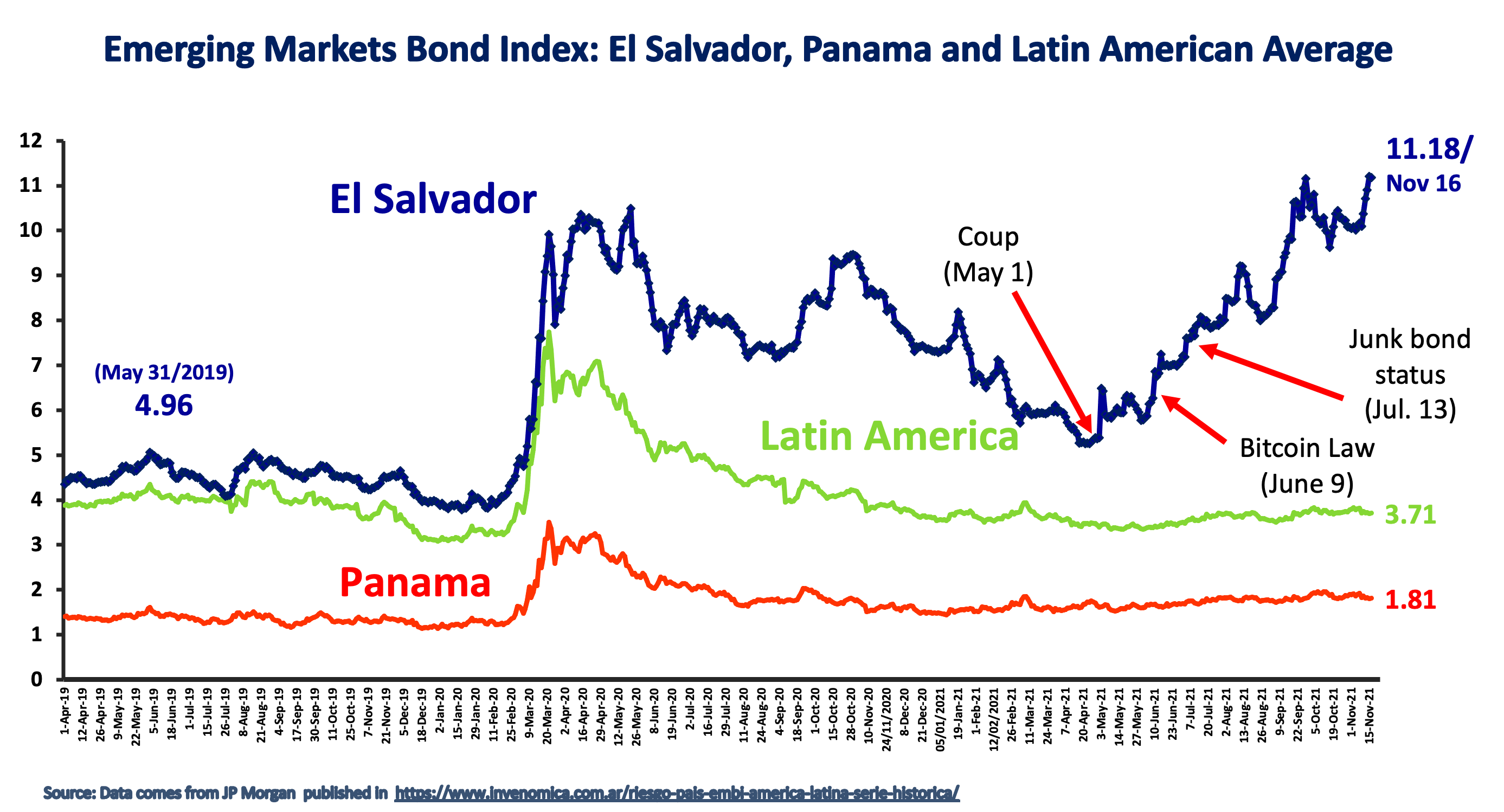

The introduction of bitcoin as a legal tender brought more uncertainty at a time when the country needed to instead build more confidence and trust. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, El Salvador’s public debt was already the main vulnerability of the economy. The problem was exacerbated due to the pandemic in 2020—public debt increased to 89.9 percent of the GDP, mostly with domestic short-term debt and external bonds. The government’s negotiation with the International Monetary Fund on an Extended Fund Facility (EFF) provided some hope that fiscal policy would improve, and the result was a four point decline in the JP Morgan Emerging Markets Bond Index (EMBI) between October 2020 and April 2021. However, due to the coup in the Constitutional Court on May 1, 2021, the Bitcoin Law, and tensions with the U.S. Government, the EMBI for El Salvador jumped above ten by September 2021 (see chart below), suggesting a lack of confidence in the country’s sovereign debt.

The Failed Introduction of Bitcoin

Within the first fifty days of Bitcoin’s introduction as El Salvador’s legal tender, several operational and regulatory failures appeared. First, to implement bitcoin as a legal tender the government had to create in a short period of time a digital wallet—software that stores user information, payments, and holdings of currencies—called Chivo Wallet. In the first months of operation, the Chivo Wallet’s system crashed several times.

Furthermore, the current bitcoin legislation leaves multiple loopholes and mandates the use of cryptocurrencies in an unconstitutional way. The Executive Branch has not complied with its constitutional obligation to discuss the law and should have trained the population in the use of bitcoin and of the Chivo Wallet application. There is also no legislation that protects personal data, leaving users vulnerable to identity theft: Chivo Wallet has already suffered from more than 2,000 cases of stolen identity. It was easy for many individuals to unlawfully use the Unique Identification Card numbers of thousands of citizens to steal the $30 subsidy offered by the government since the Chivo Wallet is not able to validate identities.

Additionally, there is little transparency in the administration of bitcoin. Making bitcoin legal tender, together with the U.S. dollar, is an element of monetary policy, which is usually run by central banks. However, the Chivo Wallet is operated by Chivo S.A. de C.V., a public limited company with variable capital owned by CEL, a state company that generates electricity from different energy sources (hydro, geothermal, and bunker or diesel). The legislature reformed the electricity legislation and CEL’s law so that the Court of Accounts cannot directly audit Chivo S.A. de C.V., which raises transparency issues. So far, nobody knows what companies built the infrastructure for the system (and at what value), who wrote the code for the Chivo Wallet, and whether there was a competitive tender to do this. At the same time, the government created a Bitcoin Trust (FIDEBITCOIN) operated by the Bank of Development of the Republic of El Salvador (BANDESAL), with initial investment capital of $150 million transferred by the Ministry of Finance to warrant the bitcoin held in the Chivo Wallet and finance the $30 subsidy for each individual. The government promises to maintain sufficient funds so that anyone who wants to exchange Bitcoin for dollars can do so at any time. These measures were taken to promote public acceptance of Bitcoin.

Instability of Bitcoin

Beyond the botched implementation, bitcoin also presents challenges as a national currency. To conceptualize these challenges, compare dollarization with “bitcoinization.” On January 1, 2001, El Salvador adopted the U.S. dollar as legal tender due to the strong economic relationship between the two countries: the United States is El Salvador’s main trade partner and source of foreign direct investment (FDI). Additionally, almost three million El Salvadorans have migrated to the United States, and in 2021 remittances will reach $7.3 billion—more than 25 percent of El Salvador’s GDP. The monetary reasons for adopting bitcoin, in contrast, are much less apparent. Before the current monetary experiment, bitcoin was almost nonexistent in economic transactions in El Salvador. While dollarization eliminated exchange rate risks and the U.S. dollar is a relatively stable currency, bitcoin is extremely volatile and introduces exchange rate risk. Dollarization also eliminated the need for currency exchanges and its fees, given that the U.S. dollar is an international reserve currency. Meanwhile, the bitcoin is still only marginally used in the world economy. The U.S. dollar is backed by the U.S. Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve, and through dollarization, El Salvador became supported by the strength of both institutions. Bitcoin, on the other hand, is distributed by a payment mechanism with no central authority backing its value. Lastly, the government has argued that with the new policy, Salvadorans will not have to pay fees when sending remittances to their families because the government’s Chivo Wallet will not charge such fees; while this is true, all costs involved in operating and managing the system will be supported by taxpayer’s money, whether they use the service or not.

Different stakeholders have expressed doubts about the use of bitcoin as legal tender. First, Salvadoran citizens, before and after passage of the law, were skeptical of the digitial currency. A survey from the Central American University José Simeon Cañas fielded between August 20 and 30 found that 95.9 percent of individuals in the sample agreed that the use of bitcoin should be voluntary, not mandatory; 71.2 percent expressed that they were interested in using only dollars, even though they could use bitcoin; and 66.7 percent answered that deputies should repeal the law. According to the monthly surveys run by FUSADES, in October 2021, 89.8 percent of firms declared that they did not have any sales with bitcoin and 76.9 percent of consumers did not make any purchases with bitcoin.

Second, some multilateral organizations have cautioned about the risks that come with adopting bitcoin as legal tender. The IMF has warned on several occasions that the risks of adopting the cryptocurrency are greater than the potential benefits since bitcoin is not a digital currency but a cryptoasset, which is unstable and unbacked. Additionally, the World Bank rejected a request from the Salvadoran government to provide technical assistance given “environmental and transparency shortcomings.” Third, as shown in the chart above, investors are concerned about the implications of the bitcoin law on debt sustainability in El Salvador.

Suggestions to Improve the Use of Bitcoin

The adoption of Bitcoin as a legal tender took everybody except for the small group of individuals involved in the design by surprise. The implementation of the Bitcoin Law was tainted by lack of public debate; lack of feedback from monetary policy experts and multilateral organizations; and lack of transparency. To correct this path, it is necessary to reform the law so that bitcoin is voluntary rather than mandatory and is not as vulnerable to abuses such as the payment of salaries or pensions as well as ensuring that there is real training in the use of virtual assets. Likewise, it is necessary to bring key stakeholders to this conversation and to make the system more transparent; for instance, publishing detailed financial information on the use of public funds for the operation of the Chivo Wallet, balance sheets, profit and loss statements, availability of reserves backing up users’ balances, numbers of stolen identities, among others. There should be a more inclusive discussion regarding the legislation that has to be approved for the implementation of bitcoin as legal tender, so there is a transparent public policy.

Meanwhile, the adoption of digital currencies is a global trend; thus, rather than taking a shortcut, the challenge is to create a path for an orderly transition to digitialization. According to the IMF, at least 110 countries are considering the introduction of central bank digital currencies. At the same time, there are many private initiatives offering stable coins—digital tokens backed by external assets. To adopt digital currencies while ensuring domestic and financial stability, countries will need to invest in infrastructure to ensure access in remote and poor areas; regulate the protection of data privacy while promoting innovation; create new ways to regulate supervision, cybersecurity, money laundering, the financing of terrorism, and environmental sustainability of new technologies; among other efforts.

. . .

Alvaro Trigueros-Argüello is the Director of the Department of Economic Studies at the Salvadoran Foundation for Social and Economic Development (FUSADES). Holds a Ph.D. in Economics and an M.A. in Development Economics from Vanderbilt University, and a Licenciate in Economics from Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas in El Salvador.

Marjorie Chorro de Trigueros is the Director of the Department of Legal Studies at FUSADES. She is Attorney of Law and was part of the negotiating team of El Salvador for the Dominican Republic Central American Free Trade Agreement (DR-CAFTA) with The United States. She is Fellow of the Central American Prosperity Project at the George W. Bush Presidential Center, and a Fellow of the Central American Leadership Initiative of the Aspen Global Leadership Network.

Image Credit: Flickr; Jernej Furman; Creative Commons 2.0 Generic License

Recommended Articles

Africa accounts for approximately two percent of global air travel. Given the continent’s vast size and large distances between major trade hubs, enhancing intra-African air connectivity will be…

An estimated 7.9 million Venezuelans migrated abroad for the long term under President Nicolás Maduro’s rule as Venezuela’s political, economic, and social crises have deepened. Alongside rising Venezuelan migration, migrants…

Amid stalled U.S. federal climate engagement and intensifying transatlantic climate risks, subnational diplomacy has emerged as a resilient avenue for cooperation. This article proposes a Transatlantic Subnational Resilience Framework (TSRF)…