Title: The Neglected Historical Origins of Global Economic Governance: A Conversation with Jamie Martin

International economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are fraught with controversy primarily because of claims from critics that their interventionist policies undermine the sovereignty of the Global South. Jamie Martin, Assistant Professor at Harvard University, brings a unique historical perspective into this debate in his recent book The Meddlers: Sovereignty, Empire, and the Birth of Global Economic Governance, which focuses on how international efforts to sway global capitalism emerged from elite political struggles and cooperation in the United States and Europe after the First World War. In this interview, GJIA discusses the potential future paths of global economic governance that prioritize “cooperation without dominance” with Martin.

GJIA: How did you come about writing your book, The Meddlers?

JM: The fundamental question posed by The Meddlers, as I began research on it, was how did the international governance of capitalism first become politically imaginable and technically feasible? My interest in this question started during the aftermath of the great financial crisis of 2007-2008 and the eurozone crisis when the history of Bretton Woods was being reconsidered and calls for renewing global economic governance were picking up. As my research progressed, the book ended up narrating the 1940s as a critical though overrated moment in a much longer history of struggle over how to govern the world economy. Moreover, I discovered in the research that institutions began to emerge well before the Second World War that were doing things that are very familiar to us today: such as making conditional financial bailout loans, overseeing investments in economic development, regulating commodity production, facilitating central bank cooperation, and so forth. Ultimately, the book aims to show that if we really want to understand the actual birth of global economic governance, we need to look back at how the First World War fundamentally reshaped the relationship between empires and the world economy in ways that provided the crucial political backdrop to these first attempts to govern the world economy.

GJIA: One of the main novelties of your book is its shift from usual narrations of Bretton Woods international organizations founded after the Second World War to lesser-known institutions and power brokers of decades prior. What are the most valuable lessons and deconstructions that this reorientation offers for contemporary understandings of how our global economic governance came to be?

JM: The conventional way of narrating the rise of global economic governance is by dating its origins to the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944, which established the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. The argument in my book, though, is something different. I claim that the coming of Bretton Woods represented a moment in which some problems with preceding systems of global economic governance were confronted but only partially overturned. These problems also came back relatively quickly and well before the 1970s, when the Bretton Woods system was overturned. Take the issue of making financial assistance loans conditional on thoroughgoing programs of domestic austerity, for instance. This practice first emerged in the early 1920s in the context of a series of bailout loans that the League of Nations arranged for some member states, primarily in Central and Eastern Europe, and mainly states that had emerged after the breakdown of the Habsburg Empire. These loans were designed to help stabilize their currencies and recover from hyperinflation. However, they were very unpopular because of the degree of intervention they involved into questions of party politics and distribution within these states. By the end of the 1920s, this kind of global governance model was seen as highly controversial and something few states would agree to.

When people designed the IMF, some agreed that the IMF shouldn’t repeat such blunt interventionism. It shouldn’t be so browbeating, and it shouldn’t bully states undergoing extreme financial distress to commit to programs of austerity during economic downturns as the price of the assistance. Bretton Woods theoretically abandoned this old-school League of Nations-style conditionality. Almost as soon as the IMF was up and running and making resources available to some of its member states experiencing financial turmoil, the practice returned. It’s not exactly the same thing, but the essential rudiments of the practice are very similar. You get a return of conditionality already by the 1950s, which expands in the decades that follow. It doesn’t take the rise of neoliberalism or the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system for this practice to reemerge. This earlier history is something that gets missed in some of these more nostalgic accounts, which claim that Bretton Woods represented a brief-lived but remarkable kind of compromise that resolved some of these older tensions.

GJIA: A frequent trend for recent historical scholarship is to view current domestic and global inequalities through the reinterpretation of these systems’ historical predecessors, such as Paul A. Kramer’s The Blood of Government on the U.S. colonization of the Philippines and Christine M. DeLucia’s Memory Lands on King Philip’s War. Would you consider your recent work a contribution to this extensive, albeit controversial, intellectual practice?

JM: One of the principal historical claims of the book is that when these early institutions of global economic governance were first emerging, this process involved a series of adaptations of older imperial practices. Some internationalists sought to do things differently in a world slowly turning against empires. Nonetheless, the institutions they created in many fundamental ways recapitulated 19th-century practices of empire in the context of a world profoundly changed by the First World War—one in which self-determination was becoming much more powerful as a political rallying cry around a world that was becoming more democratic. These first institutions acted according to a set of old assumptions. These assumptions include the idea that not all states were to enjoy a full right of non-interference in their domestic affairs or that debtors on the so-called peripheries of the global economy could be bullied until they paid exorbitant interest on their sovereign debt. Or the idea that, by contrast, strong states were to be immune from equivalent external pressures. These were common assumptions that guided how these institutions, in many instances, acted despite the self-professed commitments made by many liberal internationalists. Now, one of my book’s claims is that some of these old imperial assumptions still mark global economic governance today. It still has imperial baggage that it needs to shake off, and this fact can sometimes be downplayed in memories of Bretton Woods. One of the supposed achievements of the creation of the Bretton Woods institutions was moving beyond an older world of empires to a more cooperative U.S.-led world order. However, these accounts often fail to recognize the deep continuities present throughout and after the Bretton Woods system with an earlier era of empire dating back at least to the 19th century.

GJIA: Despite your identification of the inherent power asymmetries historically built into interwar institutions and their reproduction in current mainstays of global governance, you still strongly hesitate against reactive nationalism and autarchy. At the same time, you maintain that sufficient reform requires far more than minor adjustments to how these massive mechanisms operate. What are some examples of the ambitious international cooperation you urge for at the end of your book? What could this look like in the twenty-first century?

JM: The book, as you mentioned, should not be read at all as embracing any kind of sovereigntist or nationalist alternatives to global governance—quite the contrary. The book has a clear normative upshot; It’s to renovate, rethink, and reimagine what global economic governance should look like for the 21st century. This [reimagination] doesn’t require looking back to the institutions of the 20th century, created in a world of empires and designed to reflect the global dominance of the newest empire on the scene—namely the United States. There’s a lot of mobilization around these questions today, particularly among political leaders and activists in Global South countries. For example, Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, has recently been pushing for fundamentally new ways of thinking about channeling capital via multilateral institutions for development and green transition projects that do not recapitulate the old kind of heavy-handed conditional lending done by organizations like the IMF or the World Bank. There are calls by officials at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) and others for creating new independent sovereign debt authorities and new ways of handling debt reconstructions. These issues are particularly pressing at the current moment, given the extreme debt distress faced by many low-and middle-income countries, after the COVID pandemic and during this era of rising interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve.

Now, it should also be noted that there is growing competition among lenders in the world economy and that the global politics of debt are far more complex than ever before, as you see a vast number of different actors making claims on debtors today. This [growing competition] makes debt restructuring today far more complex and difficult than in the past. But it also means that there’s potentially an opening for new institutional practices—perhaps even for new institutions themselves. You see in the pages of the Financial Times or among leading officials in the IMF itself a real recognition that business needs to be done differently, particularly when it comes to the politics of global debt. In the book, I resisted saying precisely what these solutions would be. Instead, I hope that the history I provide is helpful in clearing some ground to think creatively and anew about what a new system might require.

. . .

Jamie Martin is an Assistant Professor of History and Social Studies at Harvard University. He was previously an Assistant Professor in the School of Foreign Service and Department of History at Georgetown University. His historical research has an international focus on political economy and war, specifically during the interwar period. In 2022, he published his first book, The Meddlers: Sovereignty, Empire, and the Birth of Global Economic Governance. He is working on his next book project on the economic consequences of the First World War outside the war’s battlefields in Europe and the Middle East.

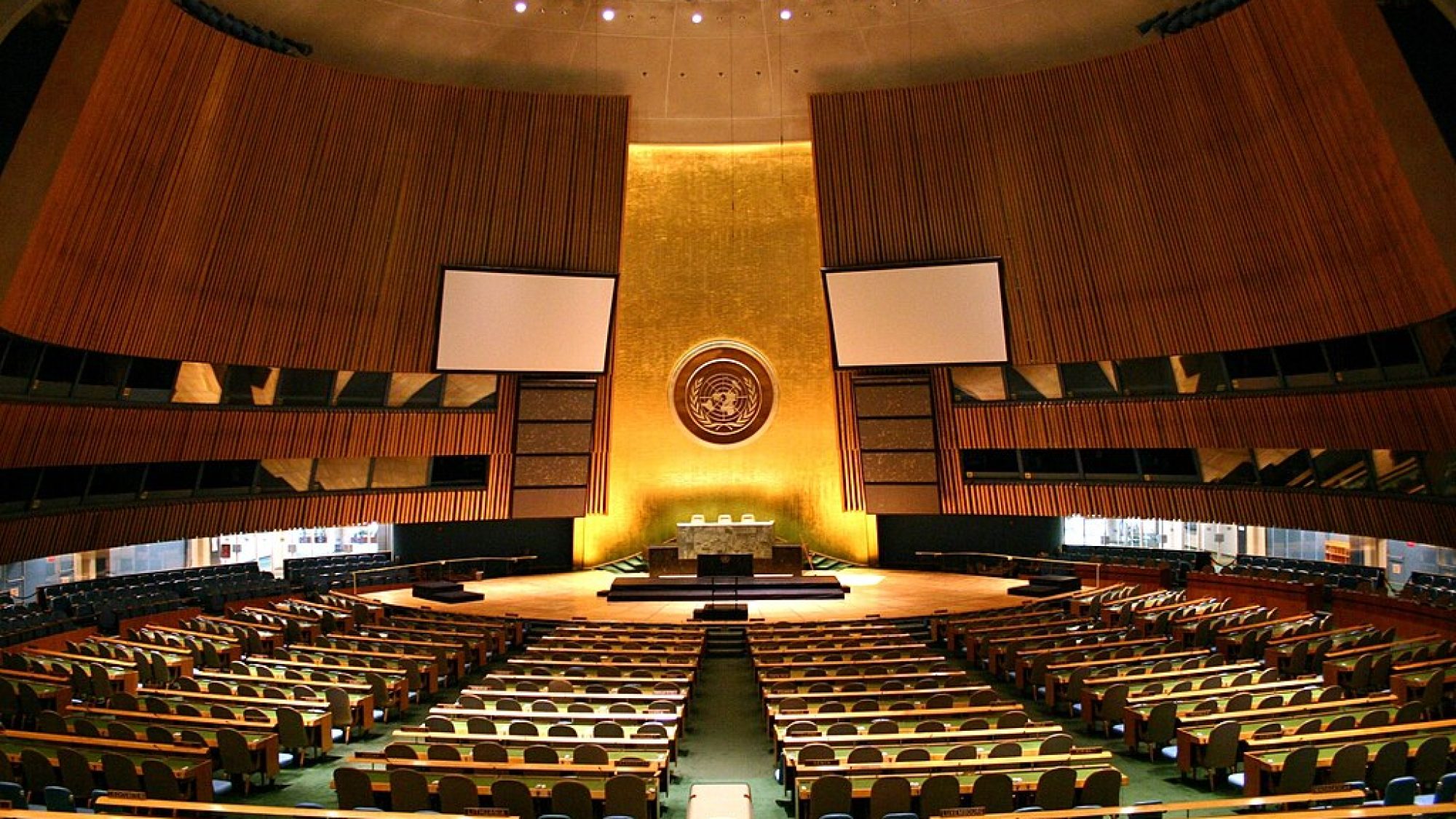

Image Credit: Patrick Gruban, cropped and downsampled by Pine, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Recommended Articles

In 1953, Kuwait established the world’s first sovereign wealth fund to invest the country’s oil revenues and generate returns that would reduce its reliance on a single resource. Since…

Cruises have increasingly become a popular choice for families and solo travelers, with companies like Royal Caribbean International introducing “super-sized” ships with capacity for over seven thousand…

In March 2025, widespread protests erupted across Türkiye following the controversial arrest of former Istanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu, an action widely condemned as politically motivated and…