Title: The Role of Sovereign Green Bonds in Chile’s Development

In 2019, Chile became the first sovereign issuer of green bonds in the Americas and the third largest issuer among emerging markets the following year. Building on the country’s climate action credentials and guided by international best practices, Chilean authorities developed a Green Bond Framework. The issuance of sovereign green bonds has allowed Chile to finance its climate agenda at a lower cost than traditional sovereign funding and with a larger and more diversified investor base. Green bond issuances can have a tangible impact for debt management offices throughout Latin America, as financing needs remain large and climate action has become even more critical.

What are green bonds?

Green bonds, issued for the first time in 2007 by the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the World Bank, represent a major financial innovation of the last fifteen years. They are now widely adopted by states, municipalities, large corporations, and non-profit NGOs. In issuing these debt instruments, the issuer commits to channeling the proceeds to finance or refinance projects that protect the environment or mitigate the effects of climate change. Green bonds usually finance investments in renewable energy, green infrastructure, and ecosystem conservation. The bonds allow for a more transparent green budgeting process and are purchased by investment funds supporting ESG (environmental, social, and governance) values. Sovereign green bond issuances have grown since the 2015 Paris Agreement with Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) for mitigating climate change amounting to $196 billion in June 2022. Sovereign sustainable, social, and green bonds in 2020 represented around 3.4 percent of the total bond issuance in developed countries and 3.8 percent in emerging markets. Compared to a control group of sovereign and corporate bond instruments, green bonds are particularly well suited to green investments due to their liquidity, (two to twenty basis points less, in some studies), low risk, ability to hedge for other assets, and issuance at long-term horizons.

Chile pioneering the issuance of green bonds in the Americas

In 2018, the Chilean Ministry of Finance (MoF) was tasked with narrowing fiscal deficits–improving the fiscal balance by moderating expenditures and boosting revenue. Separately, the MoF also sought to promote sustainable finance and development towards a low-carbon economy. Green bonds were viable instruments that met these objectives, aligning with Chile’s broader climate mitigation strategy.

In contrast to the issuance of regular bonds, Chile’s green bonds required several additional steps before they could be issued. First, the MoF developed and a Green Bond Framework in May 2019 that outlines the MoF’s obligations as an issuer. The framework was key in allowing investors to understand the processes behind green bond issuances, especially since standards in the asset class were still maturing and relatively new to investors. Working with the Budget Office and other ministries, the MoF selected and certified a set of eligible projects for the bonds, mostly in clean transportation, renewable energy, water management, and green buildings.

While Chile succeeded in following the steps required to issue these bonds, marketing the bonds to investors required a different approach. Investors were gradually becoming familiar with the new asset class and needed a guarantee on the issuer’s climate credentials. So, to establish credibility, the MoF sent regular updates to investors on its progress in the domestic ESG landscape.

The success of Chile’s green bond initiative

In addition to promoting multiple sustainable development goals, Chile’s green bonds delivered several key financial milestones. In 2020, Chile became the largest issuer of sovereign green bonds in Latin America and the third largest issuer among emerging markets. As of the end of November 2022, roughly 31 percent of the government’s debt was in ESG instruments up from 0 percent before 2019.

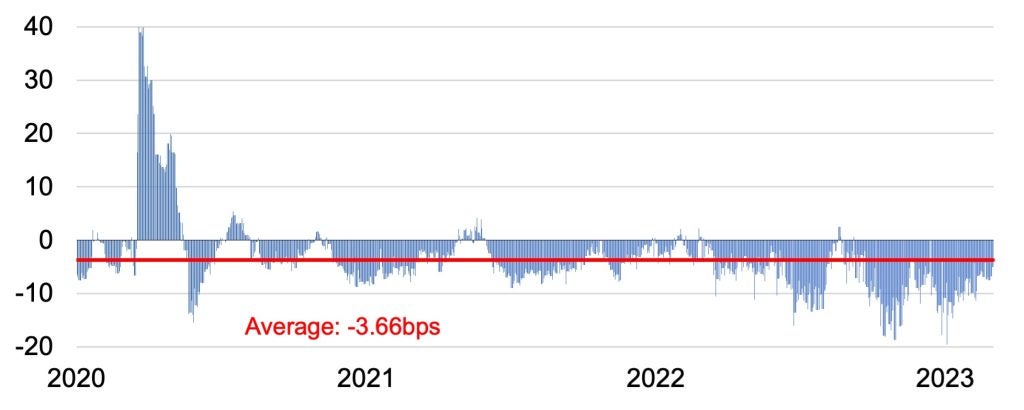

Since Chile’s bonds were issued at exceptionally low yields with negative issue premiums (below secondary market pricing), these issuances improved the country’s borrowing costs as compared to regular bonds. Investors with ESG mandates usually have a higher willingness to pay, resulting in low borrowing costs for the MoF. As shown in the figure below, some of Chile’s green bonds have traded at lower interest rates than regular bonds.

Z-Spread difference between green and regular bonds

Basis points

Source: Bloomberg data platform. Note: Plain vanilla bond maturing in 2030, Green bond maturing in 2031, using standard practice the difference in maturity is adjusted by 5bps.

Green bonds have also allowed the MoF to broaden and diversify its investor base toward investors with ESG-mandated portfolios, a desired property for debt managers. . Importantly, reflecting the financial benefits of these instruments, Chile’s green bond issuances paved the path for private issuances and set the standard for other debt management offices in Latin America, further strengthening the country’s leadership in the green finance space. In 2021, five Chilean corporations issued labeled bonds for a total of USD 3.8 billion. In the aftermath of Chile’s green bond issuances, other Latin American countries followed with Colombia issuing green bonds in 2021 and Mexico and Uruguay issuing ESG-related bonds.

The MoF’s success with green bonds has been recognized with several awards. However, most impressively, the MoF broadened the issuance of ESG bonds, allowing Chile to reach its climate targets. After becoming the first sovereign to issue green bonds in the Americas, Chile became the first country to issue a Sustainability Linked Bond (SLB) in March 2022. In contrast to green or social bonds, in which expenditures are related to specific projects, an SLB’s coupon payment is directly related to the issuer achieving a given outcome. Chile’s 2022 SLB framework aims to achieve targets for greenhouse gas emissions[1] and at least 60 percent of energy produced by renewable sources by 2032 (up from 27% in 2021). If Chile fails to meet its target, the bonds pay an additional coupon, creating an incentive to make progress on the targets.

Moving Forward

Chile’s experience as a trailblazer in the green bond market delivers important lessons. Green bonds sovereign issuers to demonstrate their commitment to sustainable finance and climate action, while lowering their borrowing costs and diversifying their investor base. Green bonds also contribute to financing the transition to a more sustainable low-carbon economy.

However, climate action should not only focus on green infrastructure but also on carbon pricing initiatives that provide incentives for the private sector to reduce environmental waste and greenhouse gas emissions. Low-income families would benefit from public expenditures to reduce environmental costs because low-income families are more affected by air pollution, extreme heat, and environmental disasters. Climate change is estimated to have a greater impact on low-income nations and developing economies. Potential climate-related losses in Chile are estimated to reach 11 percent of the GDP by 2100 with almost 40 percent of its real estate exposed to climate risks. These economic losses disproportionately affect poor families, particularly workers in agriculture and fishing.

As an emerging economy, Chile must make both public and private investments in green infrastructure. Fiscal spending on environmental protection in Chile and Latin American countries represents just 0.1 percent of the GDP, well below the 1 percent spent by many advanced economies such as Japan, France, and Italy. A recent study estimates that to fight the climate crisis, Latin American countries spend annually between 2 percent and 8 percent of their GDP. Low-cost green bond issuance should help developing countries like Chile gather the funds necessary to invest in public infrastructure. Hence, Latin America would benefit from strengthening its commitment to climate action with the issuance of green bonds and other ESG financing.

Green bond issuance must be complemented by issuers enhancing accountability and maintaining credibility on their commitments to climate action, as these also support lower borrowing costs. Particularly, the periodic publication of audited reports regarding the allocation of funds and the impact of these funds is key. Implementing green bond reports and transparency initiatives such as the InterAmerican Development Bank’s Green Bond Transparency Platform (GBTP) would further enhance investor confidence. Furthermore, countries should build an accounting system for their “natural capital” to better document their preservation of the environment, as Chile and the UK have done in recent years.

Although further action is necessary, green bonds are now a fundamental part of countries’ sovereign tools. They can help fund infrastructure for climate action while lowering sovereign funding costs.

[1] The targets consider annual greenhouse gas emissions of 95MtCO2e by 2030, and a maximum greenhouse gas budget of 1,100 MtCO2e between 2020 and 2030.

…

Carlos Madeira is a senior economist at the Bank for International Settlements and the Central Bank of Chile. His research is specialized in Household Finance, Macroprudential Policy and Climate Change. His views are his own and do not necessarily represent the Central Bank of Chile or the BIS.

Andrés Pérez is Chief Economist for LatAm economies, except for Brazil, at Itaú. Andrés was formerly the Head of International Finance and Head of Advisors at the Ministry of Finance of Chile, where he led the issuance of sovereign green bonds, among other initiatives between 2018 and 2021. His views are his own and do not necessarily represent Itaú.

Image Credit: Climate & Clean Air Coalition

Recommended Articles

This article contends that South Africa’s 2025 G20 presidency presents a critical opening to shape governance of critical mineral supply chains, essential for renewable energy, digital economies, and national…

Germany’s economy is being throttled by a more competitive China that has usurped its previous manufacturing dominance in many industries. In response, Germany has doubled down on the China bet…

In 2021, the European Union (EU) attempted to assert itself in the Indo-Pacific arena to increase its geopolitical relevance by releasing an ambitious and multifaceted Indo-Pacific Strategy. However, findings from…