Title: Making Anti-Racism the Core of the Humanitarian System: A Review of Literature on Race and Humanitarian Aid

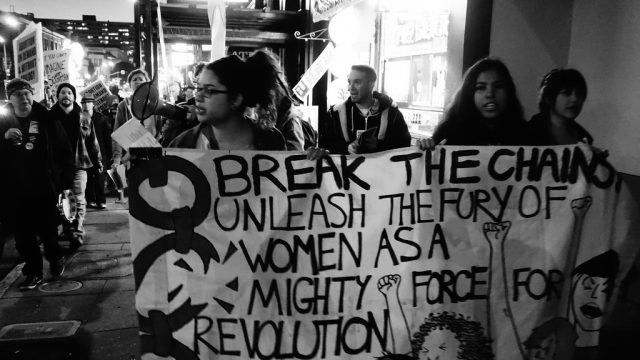

In the wake of the senseless murders of George Floyd and too many others, we must call on the international community to reimagine the institutions that enable systemic racism. Amid a global call for racial justice, the humanitarian system must hold itself accountable for change. The fight against implicit bias in the aid sector requires anti-racism to be the core of humanitarian work.

In a July 2020 internal statement signed by 1,000 staff members of Médecins Sans Frontéres (MSF), workers criticized the NGO’s “dehumanizing” programs, run by a “privileged white minority.” MSF, widely respected and the winner of the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize, is only one of many organizations grappling with its role in perpetuating racism. Though MSF hired ninety percent of staff last year locally, senior managers are largely European. Those closest to the conflict are shut out of the decision room, fueling the savior mentality that is unproductive in humanitarian response. From the 2010 Haiti earthquake to Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines, Westerners assuming they knew best often made decisions that fail to address the local population’s needs.

Literature Review: The Racist History of Humanitarianism

With roots in imperialism and colonialism, the humanitarian system must begin confronting its racist history that continues to shape aid today. In the article “The Humanitarian Global Colour Line,” Professor of International Affairs and Political Science Michael Barnett explains that as humanitarianism has evolved, so has “the location of race in maintaining what W.E.B. Dubois famously called the “global color line.” The global color line,” defined by DuBois as “the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea,” was the problem of his time at the dawn of the twentieth century. By placing the “global colour line” in the context of Black Lives Matter protests, Barnett demonstrates that it is as relevant today as ever before.

Barnett emphasizes that resistance to localization stems from colonialists attempting to “civilize” indigenous populations through imposing Western ways of life, from forced religious conversion to damaging economic systems. Decolonization was a façade for the introduction of new structures to maintain Western superiority. Instead of white men with guns, today’s world has white men with money. Like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, institutions based on the Bretton Woods Agreement trap developing nations in poverty. In Africa and Latin America, conditioning loans on reform––fiscal austerity, high interest rates, open markets and trade liberalization––benefits the institution while devastating the local economy.

In July, The New Humanitarian interviewed activists, aid workers, and analysts on how “#BlackLivesMatter and the COVID-19 pandemic are exposing the hypocrisies and structural problems that have long underpinned international humanitarian action.” The discussion was summarized in the article “The West’s Humanitarian Reckoning,” which thoroughly examined issues including ignoring problems at home, narratives of need, the politics of being apolitical, de-funding international institutions, and more. Degan Ali, the CEO of Kenya-based NGO Adeso, and Angela Bruce-Raeburn, regional advocacy director for Africa at the Global Health Advocacy Incubator in Washington, DC and member of Black Women in Development, spoke about how the old guard of humanitarianism has prevented promises of change from becoming tangible progress. Building on the points made by Barnett, Ali shared how language employed by the aid industry when responding to crises masks “UN Security Council decisions (or lack thereof) and Western-led extractive industries that have kept so-called developing countries in debt and in crisis.”

While the Black Lives Matter movement sparked important dialogue on race, few individuals are talking about how the structure of the aid system keeps developing countries in poverty. Racism is as much a part of the international humanitarian architecture as it is part of American institutions. Similar to colonialism, the power dynamics of international aid are designed to ensure inequalities. Though NGOs may hire local staff, they are kept from positions of power that would give them a seat at the table––and those who are given a seat rarely get a voice. Reflecting on her time at Oxfam, Bruce-Raeburn called out the culture of white supremacy in aid. “When white men talk in these NGO meetings, it’s like [they are] the voice of God,” said Bruce-Raeburn.

The world needs a new approach to global humanitarianism. In the article “Decolonising Aid, Again,” Paul Currison offers an in-depth analysis on how policymakers can build a new model for humanitarian aid that places anti-racism at its center. National staff are expected to adapt to international norms, even when they are culturally inappropriate or politically ineffective. This deep-seated racism prevents humanitarians from achieving their objectives on the ground. The deliberate lack of communication and coordination with local communities ensures that the balance of power stays tipped towards the international sector.

“COVID-19 Changed the World. Can It Change Aid, Too?” by Jessica Alexander adds to Currison’s dialogue on the need to rethink humanitarianism. This article analyses how crises become moments of change, exploring the impact of genocides, wars, and natural disasters on the way aid agencies operate. Beginning with the Rwanda genocide in 1994, Alexander demonstrates the gap between Westerners and the communities they are attempting to help. Aid workers assumed superiority resulted in being out of touch with the population’s actual needs, often leading to little to show for months of work.

In Haiti, local organizations were excluded from English and acronym-speak meetings. Throwing money around–– an unprecedented $13 billion––is as good as nothing when it goes to all the wrong places. A Port-au-Prince community established a neighborhood committee system within two days of the earthquake, equipped with food, nurses, supplies and security. Yet, white aid workers–– and celebrities with no experience––viewed Haitians as incompetent and incapable. “Haiti’s Disaster after the Disaster: The IDP Camps and Cholera” by Professor of African American Studies and Anthropology Mark Schuller offers greater insight into what went wrong. This article, published in the Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, focuses on the flaws of the international community’s response in Haiti. Rather than directing funds towards rebuilding the elected Haitian government’s capacity, major donors like the United States and United Nations funneled money to strengthen NGOs. The Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) cluster, the only cluster headed by a Haitian government agency, was the most effective. The fact that this cluster had “the most hand-on, local, empowerment-oriented approach” is telling of how the humanitarian system missed the mark in more places than Haiti.

Alexander shares several more examples of crises where exclusion of local humanitarian actors led to futile efforts. In 2013, Western aid agencies again made the mistake of underestimating local responders after Typhoon Haiyan killed over 6,300 people in the Philippines. Though the Philippines is a middle-income country with a highly skilled civil society, the culture of Western superiority persisted. Despite locals having the cultural, political, and linguistic knowledge necessary to make decisions in times of crisis, international organizations overwhelmed the national response. While local organizations quickly provided cash assistance that allows Filipinos to rebuild their homes and businesses, bureaucratic red tape bogged down Western aid agencies.

Learning a New Language

Without a shared language to discuss racism, humanitarians have long been able to evade the conversation. Terms like “localization” and “accountability to affected people” attempt to solve this problem without altering the power structures that enabled it. This language obscures the reality that few changes have been made, and more inclusive policies have been largely symbolic or implemented poorly.

Though many countries view racism as an American problem, discrimination pervades communities across the globe. However, anti-racism work that looks the same everywhere does good nowhere. Training courses, workshops, and conferences on anti-racism developed in American language carry the legacy of colonialism forward. In countries where racism is embedded in structures inherited from colonial structures, this corporatized form of anti-racism will only further cement these institutions.

Challenge and Change

The humanitarian system designed in the post-World War II era has fallen short. As new challenges emerge––climate change, a growing refugee crisis, endless civil wars, technologically advanced terrorists––we must envision a humanitarian sector ready to take on the increasingly complex emergencies of the twenty-first century.

And then we must hold ourselves responsible for doing the difficult work it will take to get there.

Reforming the system begins with inclusivity––more voices, more ideas, and more innovation. Above all else, humanitarian organizations need to prioritize more diverse leadership. Anti-racist work that excludes people of color is racist. For once, white people need to give up their seat at the head of the table. Choosing to ignore the right people is the repeated failure of aid organizations. We need to listen more than we speak and give more than we take. By viewing the Global South as helpless, Westerners have preserved the economic and political structures they benefit from. By recognizing those most affected as agents of change, we can build a humanitarian system equipped to respond to simultaneous crises. In addressing aid’s racist past to create local resilience, we hand the power to the individuals who have a stake in their country’s success even after the foreigners return home.

With the humanitarian system’s future at stake, this is a mistake aid organizations cannot afford to make.

. . .

Carly Kabot is a sophomore in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University studying International Politics and Religion, Ethics and World Affairs. She is from Rye Brook, New York.

Image Credit: Julien Harneis, Wikimedia, Creative Commons License

Recommended Articles

Books about foreign aid are often written from the perspective of donor countries, especially the United States. In Aid Imperium, a new book…

Feminist theory confronts researchers with a unique series of hurdles. While other schools of thought draw upon vast sources of evidence, the feminist approach remains largely theoretical. Feminist…

Current discourse among scholars and practitioners of international affairs focuses heavily on multilateral institutions such as the European Union (EU), the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the…